All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The pso Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the pso Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The pso and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The PsOPsA Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported by educational grants. We would like to express our gratitude to the following companies for their support: UCB, for website development, launch, and ongoing maintenance; UCB, for educational content and news updates. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis content recommended for you

Psoriatic arthritis: An overview

Do you know... Early psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is defined by diagnosis within how many years from the start of the first PsA symptom?

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a common inflammatory condition, that often occurs alongside psoriasis (in around 30% of individuals with psoriasis).1 Inflammation can be systemic and can result in permanent damage to the joints.1 Patients with PsA experience a heterogeneous disease course, with many different disease manifestations, including peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, spondylitis, sacroiliitis, and psoriatic nail disease.1

Etiology2

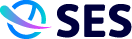

PsA occurs through a combination of factors, such as genetic pre-disposition, environment (e.g., stress), and immune responses (Figure 1). There is a genetic contribution to PsA, with a recurrence rate in siblings and first-degree relatives of 30–55%. There is evidence to suggest that disease expression of PsA is affected by the presence of specific HLA-B alleles; the presence of these alleles (especially HLA-B*08, B*27, B*38, and B*39) has been associated with various subphenotypes. Genetic variants in psoriasis may be shared with PsA; therefore, patients with psoriasis are at increased risk of developing PsA.

Figure 1. Risk factors for psoriatic arthritis development*

*Data from O’Rielly, et al.2 Created with BioRender.com

Epidemiology1

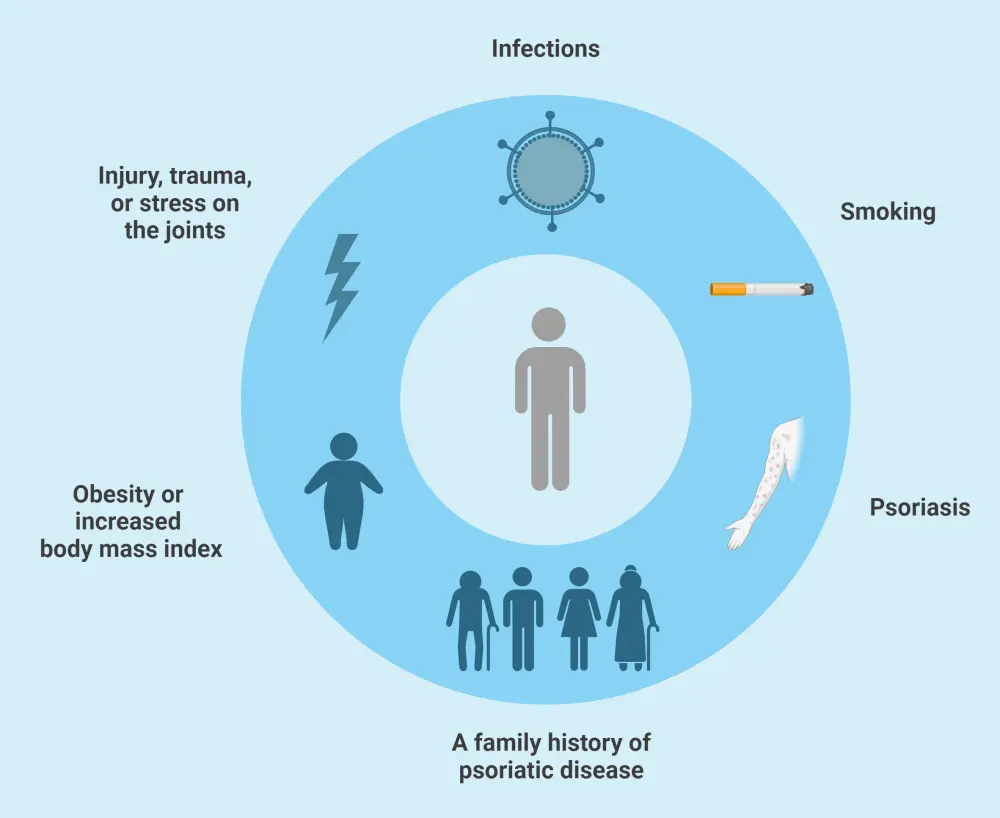

The prevalence of PsA is 0.06–0.25% in the United States, and in Europe it is in the range of 0.05–0.21%. Studies suggest that the prevalence of PsA may be lower in Asia and South America, although this may be due to underdiagnosis. Data on PsA epidemiology is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Psoriatic arthritis epidemiology*

*Data from Ogdie, et al.1

Pathophysiology

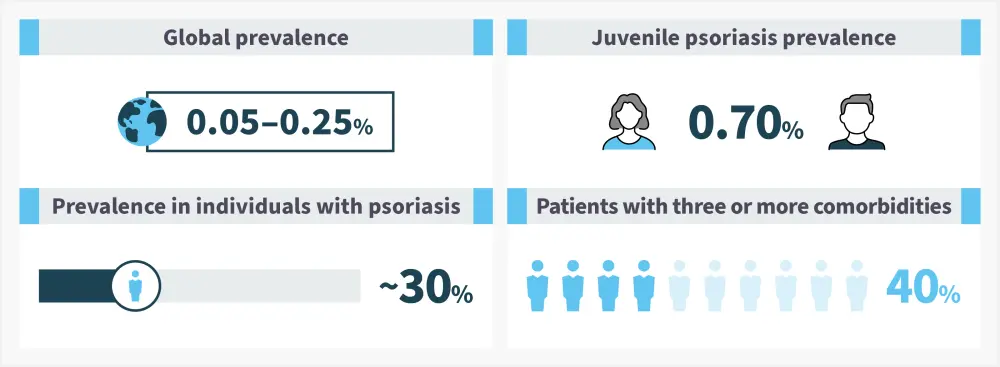

The pathophysiology of PsA is not fully understood but is underpinned by cytokine and immune cell responses (Figure 3). In joints affected by PsA, there are increased levels of T cells and cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6, -12, -17, and -23.3 This drives osteoclast activation and inflammation within the joint.3

Figure 3. Psoriatic arthritis pathophysiology*

CD, cluster of differentiation; DC, dendritic cell; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; RANK, receptor activator of nuclear factor-кB; Th, T helper; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TNFAIP, TNF alpha-induced protein 3; TNIP, TNFAIP3-interacting protein 1.

*Data from Nograles, et al.4

Signs and symptoms5

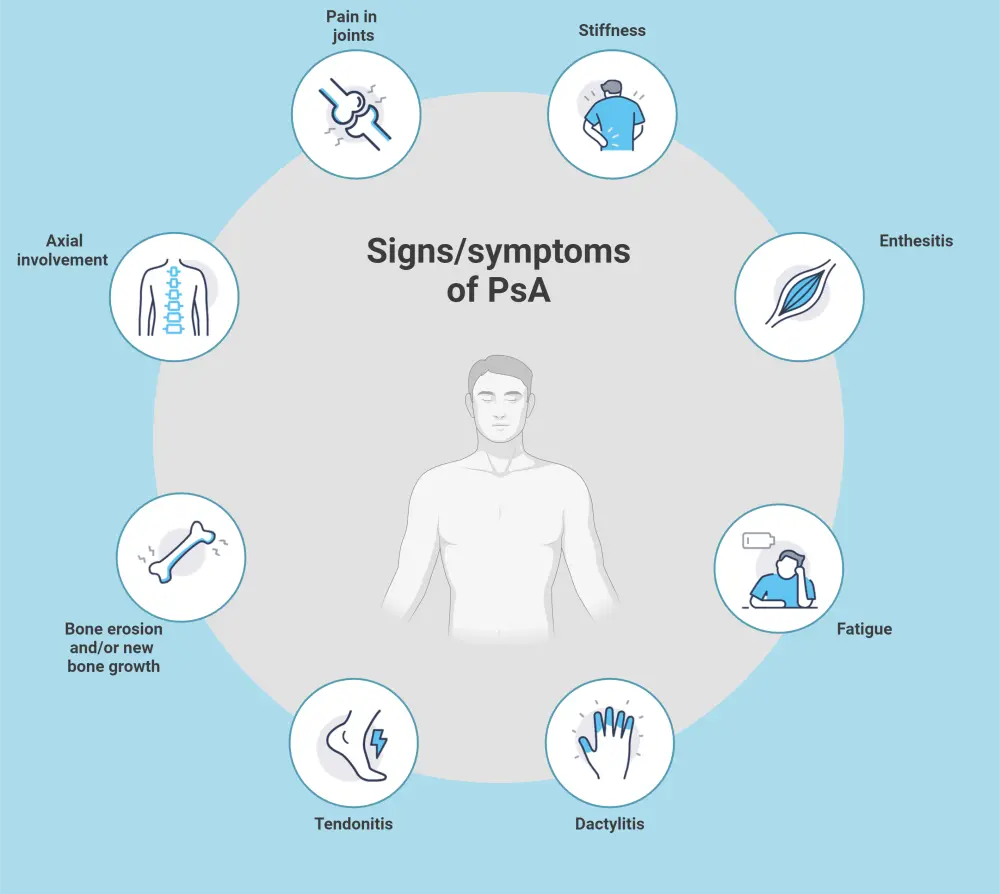

A range of domains can be involved in PsA, including peripheral arthritis, dactylitis, enthesitis, psoriasis, psoriatic nail disease, and axial disease. For this reason, individuals with PsA can present with a variety of symptoms (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Signs and symptoms of PsA*

PsA, psoriatic arthritis.

*Data from Gottlieb, et al.5 Created with BioRender.com.

Diagnosis

Peripheral arthritis, axial arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, psoriasis, and psoriatic onychodystrophy show variable prevalence and severity in patients with PsA.5 As a result, to assess a patient for PsA it is necessary to evaluate disease activity and damage across all affected regions and what impact it has on functional capacity, symptoms, quality of life, and any associated comorbidities.

Screening for PsA relies on the use of screening tools such as the Early Arthritis for Psoriatic Patients, Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Evaluation, and the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Questionnaire, which have a high specificity and sensitivity.

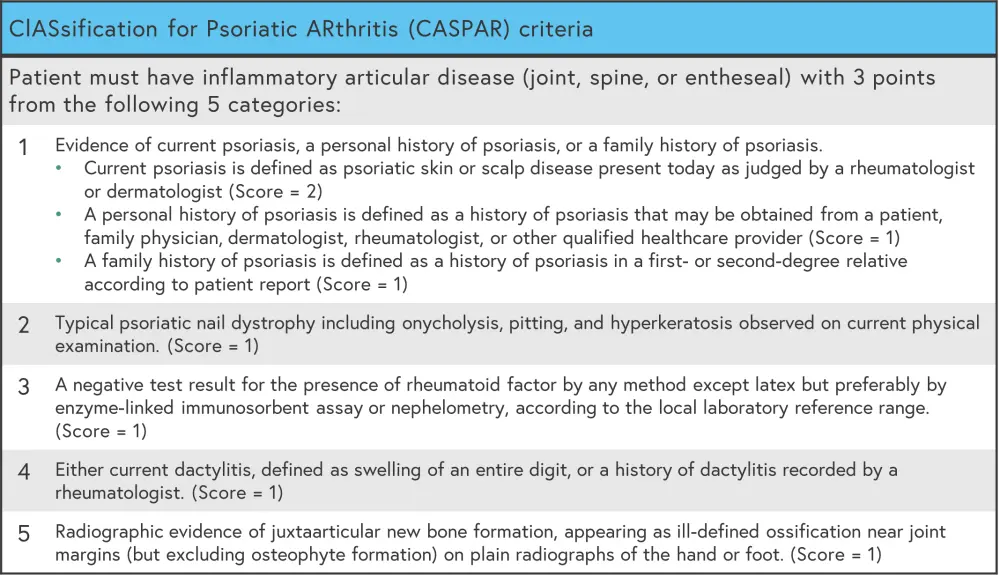

Diagnosis of PsA is based on evaluation of the patient’s history combined with physical examination. Imaging and laboratory workups can support the diagnosis.5 The classification criteria for PsA (CASPAR) can help to diagnose PsA.6 It states that patients must have inflammatory articular disease (joint, spine, or entheseal) and 3 points from five categories (Figure 5) to meet the criteria for a PsA diagnosis.6 As such, PsA can be diagnosed even if rheumatoid factor is present and psoriasis is absent.6

Early PsA is defined as PsA that is diagnosed within 2 years from the start of the first symptom.1 When PsA is diagnosed and treated within this early stage, there is evidence that patients experience less disease progression and better outcomes. Underdiagnosis of PsA is a challenge that needs to be overcome.1

Figure 5. CASPAR criteria*

CASPAR, classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis.

*Data from Antony, et al.6

Management

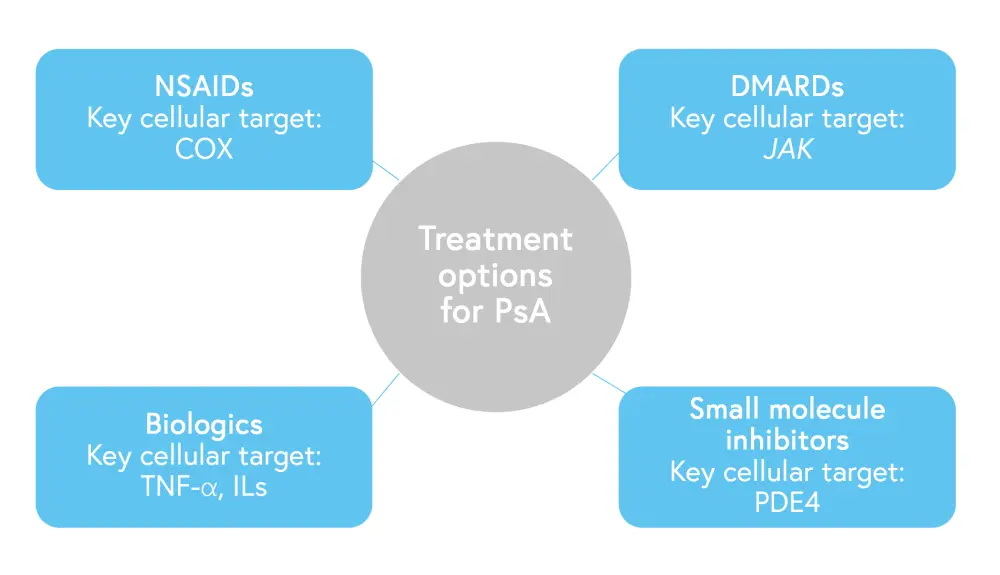

Choosing a treatment for PsA should be based on the symptoms that most affect each patient and the domains involved.5 Shared decision-making, with patients at the center of the decision-making process, is important. The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) have developed sets of recommendations for the management of PsA. Further key guidelines can be found below. Of note, guidance may vary between countries. In general:

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are used to control pain and inflammation in patients with enthesitis.

- Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs can be used in patients with dactylitis and/or nail and skin involvement.

- Biologics are recommended for use across all PsA domains.5

Treatment classes for PsA and their key cellular targets are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Treatment options for PsA*

COX, cyclooxygenase; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; IL, interleukin; JAK, Janus kinase; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PDE, phosphodiesterase; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

*Data from Gottlieb, et al.5

A key drug approval timeline for psoriasis can be found here. Guidance on management may vary between countries; see key guidelines section.

Over 50% of patients with PsA will experience at least one comorbidity, which contributes to the disease burden.3 When considering treatment options for PsA, comorbid conditions should be considered. The GRAPPA guidelines include a treatment schema that addresses some associated conditions.3

Comorbidities that affect patients with PsA, include3:

-

- hypertension;

- diabetes;

- obesity;

- mental health complications;

- Crohn’s disease;

- ulcerative colitis; and

- metabolic syndrome.

Key guidelines and organizations

EU guidelines

- European Medicines Agency: Guideline on Clinical Investigation of Medical products for the Treatment of Psoriatic Arthritis

- European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR): EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2019 update

US guidelines

- Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA): Updated treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis 2021

- American College of Rheumatology guideline: Psoriatic Arthritis Guideline

UK guidelines

- British Society for Rheumatology: The 2022 British Society for Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis with biologic and targeted synthetic DMARDs

Chinese guidelines

- Chinese Rheumatology Association: Recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of psoriatic arthritis in China

Patient organizations

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with plaque psoriasis do you see per month?