All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The pso Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the pso Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The pso and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The PsOPsA Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported by educational grants. We would like to express our gratitude to the following companies for their support: UCB, founding supporter. The funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis content recommended for you

Editorial theme | Challenges and opportunities in the early diagnosis of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis

Do you know... What is the average PsA diagnostic delay in patients with psoriasis?

Early diagnosis of both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) remains a challenge in clinical practice. A diagnosis of psoriasis is reliant on the clinical presentation of the disease, which varies between patients and can be mistaken for other skin conditions.1 On average, the estimated diagnostic delay is 1.6 years in patients with psoriasis, leading to a decline in a patient quality of life.1

PsA occurs in ~6–41% of individuals with psoriasis but it can also occur in the general population. It is estimated that PsA can cause functional impairment and decreased quality of life in up to 60% of patients, making early diagnosis of the disease a priority.2

In this first article in our editorial theme on the delayed diagnosis and misdiagnosis of psoriasis and PsA, we provide an overview of the challenges in diagnosing psoriasis and PsA, including improvements to diagnostic tools allowing for the early detection of PsA. The key highlights presented are based on two case control studies published in British Journal of General Practice by Abo-Tabik et al.1 and a review published in Expert Review of Clinical Immunology by D’Angelo et al.2

Psoriasis1

These were two retrospective, matched case-control studies using patient data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), comprising primary care health records from 796 general practice surgeries in the UK. The first study, CPRD GOLD, included a total of 17,320 patients with psoriasis and 99,320 controls; the second study, CPRD Aurum, included 11,442 patients with psoriasis and 65,840 controls.

Patients were included if they had a diagnosis of psoriasis between January 2010 and December 2017, with each patient matched to six controls without a diagnosis of psoriasis. The matching was based on year of birth, sex, and the registered general practice. The index date was defined as the date of a confirmed psoriasis diagnosis.

Results from CPRD GOLD and Aurum

In CPRD GOLD study, 52% of the cases and controls were female and 48% were male with a median age of 51 years (interquartile range [IQR], 36–64). In CPRD Aurum study, 52% of the cases and controls were female and 48% were male, with a median age of 50 years (IQR, 35–64). The baseline characteristics in both CPRD GOLD and Aurum were similar between patients and the matched controls.

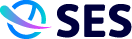

Patients with psoriasis were more likely to visit their doctor compared to the controls. The visit to the general practice increased by 60% from 1-year to 5-year period before the index date for patients with psoriasis (Figure 1) while the increase was less noticeable in the controls.

Figure 1. Average GP visits prior to the index date*

GP, general practice.

*Adapted from Abo-Tabik, et al.1

Compared with the controls, patients with psoriasis were more likely to be diagnosed prior to the index date, with either

- pityriasis rosea;

- seborrheic dermatitis;

- tinea corporis;

- candida dermatoses; and

- eczema.

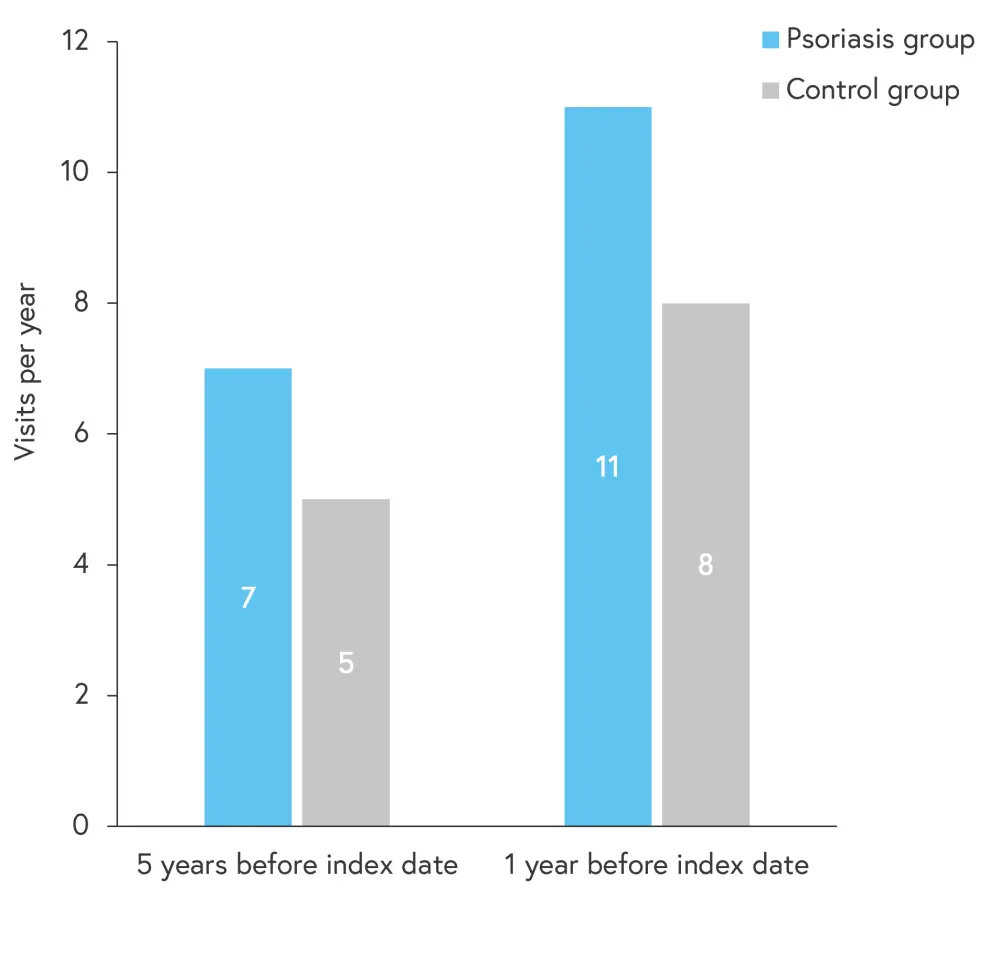

In addition, patients with psoriasis were more likely to suffer from skin-related symptoms compared with controls, with symptoms most likely to occur closer to the index date (Figure 2). At 6 months prior to the index date, patients with psoriasis were 2.3 and 2.5 times more likely to receive topical antifungals and topical corticosteroids, respectively, compared with the controls.

Figure 2. IRR of skin-related symptoms prior to the index date*

IRR, incidence rate ratio.

*Adapted from Abo-Tabik, et al.1

CPRD Aurum showed similar results to CPRD GOLD, including incidence rates of skin-related symptoms.

Psoriatic arthritis2

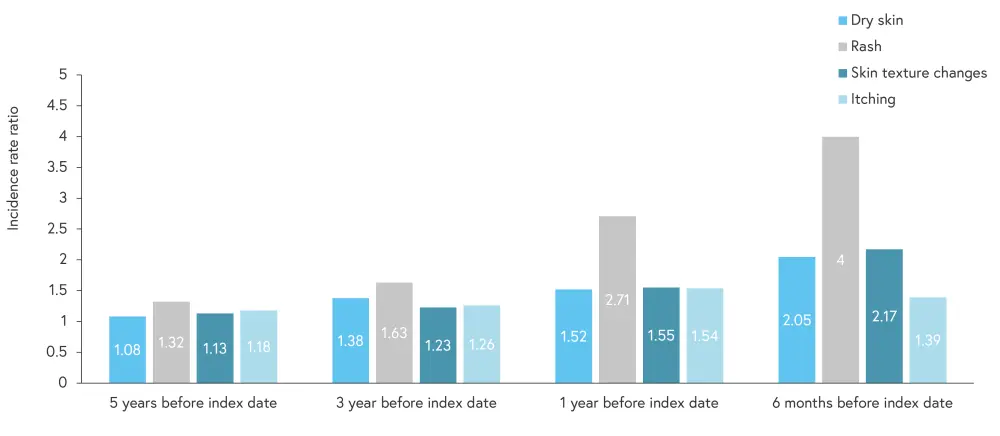

Most patients with PsA will develop skin and nail lesions either before or at the time of musculoskeletal symptoms. Primary care physicians and dermatologists can play an important role in the early identification of PsA and subsequent referral to rheumatologists. However, in a systematic review, 15.5% of patients with psoriasis who visited dermatologic centers had undiagnosed PsA; this suggests that dermatologists have limited time to undertake the routine identification of musculoskeletal symptoms. Screening tools can assist dermatologists in identifying PsA; however, not all are effective in identifying patients with early signs of disease or unusual manifestations. An overview of the main PsA screening tools is shown in Figure 3.

Clinical manifestations of PsA can vary, making diagnosis a challenge. Patients with PsA may present with oligo-polyarthritis, enthesitis, tenosynovitis, dactylitis, or axial skeleton manifestations. Of these, the most frequently occurring manifestation is peripheral enthesitis, affecting around half of individuals with PsA. Patients with PsA may also have inflammatory back pain, which occurs in approximately 25% of patients. Therefore, a diagnosis of PsA should be considered for every patient with psoriasis or when a family history of psoriasis shows peripheral arthritis (particularly if oligoarthritis or involving the distal interphalangeal joints, and/or peripheral enthesitis, tenosynovitis, dactylitis, inflammatory spinal pain).

Figure 3. PsA screening tools*

EARP, Early Arthritis for Psoriatic patients; PASE, Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Evaluation; PASQ, Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Questionnaire; PEST, Psoriatic Epidemiology Screening Tool; ToPAS Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen.

*Adapted from D’Angelo, et al.2

Screening tools are often used in the diagnosis of PsA due to the lack of specific laboratory tests. Although patients with PsA may present with abnormalities, such as an elevated C-reactive protein and increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate, these are only seen in approximately half of patients with PsA. Genetic testing also lacks predictive value and is therefore of limited utility in the diagnosis of PsA. Discovery of new biomarkers to detect PsA in the future may assist with earlier diagnosis and management.

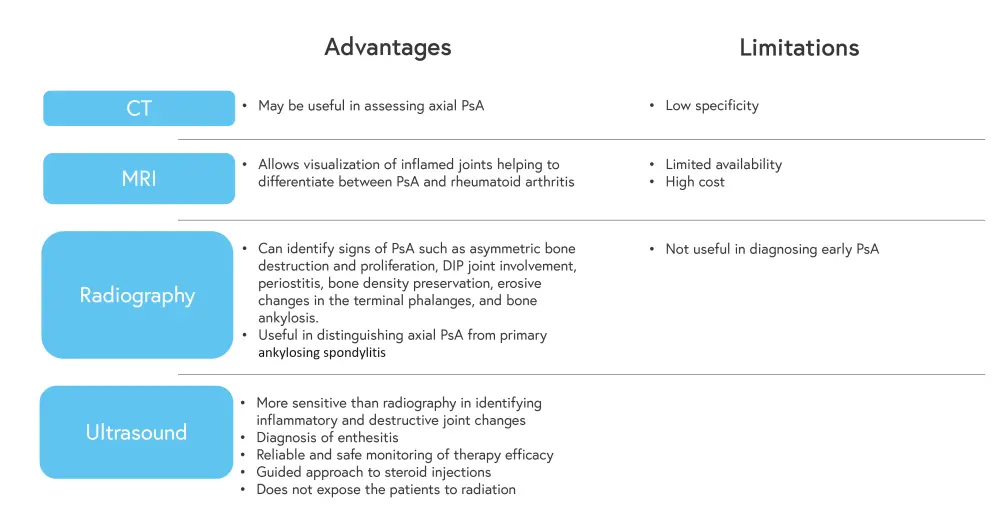

One of the most common tools used in the diagnosis of PsA is imaging. The advantages and limitations of each imaging technique are shown in Figure 4. The European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) recommend that in patients with peripheral involvement and psoriasis or a family history of psoriasis, ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging should be used.

Figure 4. Advantages and limitations of imaging techniques in PsA*

CT, computerized tomography; DIP, distal interphalangeal; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PsA, psoriatic arthritis.

*Adapted from D’Angelo, et al.2

Conclusion

Data from the studies above demonstrate that early diagnosis of both psoriasis and PsA remains a challenge. The study by Abo-Tabik et al. showed that patients with psoriasis are more likely to visit their doctor before their diagnosis, and more likely to be diagnosed with other skin conditions before being diagnosed with psoriasis. These patients are also more likely to receive a topical corticosteroid or antifungal treatment, potentially masking their psoriasis symptoms leading to a delayed diagnosis.

D’Angelo et al. showed that the use of magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound, increased referral to rheumatologists, and new treatments have improved diagnosis of PsA. Despite this, PsA remains underdiagnosed in patients with psoriasis, and implementing a screening tool which is able to identify early predictors of psoriasis may improve diagnosis. Early diagnosis of both psoriasis and PsA should be a priority for clinicians to improve patient quality of life.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with plaque psoriasis do you see per month?