All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The pso Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the pso Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The pso and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The PsOPsA Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported by educational grants. We would like to express our gratitude to the following companies for their support: UCB, for website development, launch, and ongoing maintenance; UCB, for educational content and news updates. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis content recommended for you

How to diagnose and classify psoriatic arthritis

Do you know... The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) and Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) are typically used to assess which PsA disease domain?

Diagnosis and classification of psoriatic arthritis

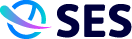

The definition of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) has evolved over time. Following the incomplete application of the definition of PsA introduced by Moll and Wright, “psoriasis associated with inflammatory arthritis (peripheral arthritis and/or spondylitis) and ‘usually’ a negative serological test for rheumatoid factor”, the CLASsification for Psoriatic ARthritis (CASPAR) study group developed novel criteria, as listed in Figure 1. This criterion allows for a PsA diagnosis to be made even if rheumatoid factor is present and psoriasis is absent.1

Figure 1. The ClASsification for Psoriatic ARthritis (CASPAR) criteria*

*Adapted from Antony and Tillett.1

The CASPAR criteria may not account for early PsA due to the low prevalence of radiographically visible damage that occurs early in the disease course. Another limitation of the CASPAR criteria is the lack of definition around what constitutes inflammatory joint, spinal, or entheseal disease. The lack of a definition for axial PsA if of particular concern and is felt to represent a key unmet need.1

Assessment1

Peripheral arthritis, axial arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, psoriasis, and psoriatic onychodystrophy show variable prevalence and severity in patients with PsA. As a result, to assess a patient for PsA it is necessary to evaluate disease activity and damage across all affected regions and what impact it has on functional capacity, symptoms, quality of life (QoL), and any associated comorbidities.

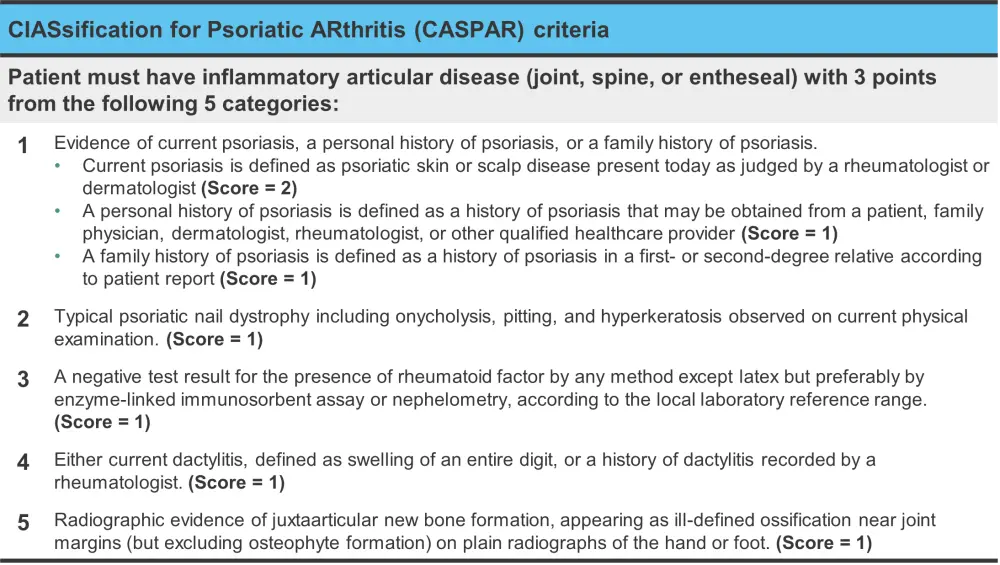

The Outcome Measures in Rheumatology Clinical Trials (OMERACT) group and the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) have established a core set of domains that should be assessed in all randomized control trials and longitudinal observational studies (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Core domain set for psoriatic arthritis*

LOS, longitudinal observational studies; QoL, quality of life; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

*Adapted from Antony and Tillett.1

†Evidence for inhibition of structural damage should be required at least once during the development program of a new medication, but is not required in all RCTs and LOS.

Domain-specific instruments1

Peripheral arthritis

Peripheral joint involvement differs between PsA and rheumatoid arthritis (RA); a significant proportion of patients with PsA have oligoarticular disease of large joints and involvement of the distal interphalangeal joints of the hands and feet. The 66/68 swollen and tender joint count instrument for peripheral arthritis is a preferred instrument for patients with PsA compared with the 28 tender and swollen joint count used for RA. While the 66/68 assessment instrument may be time-consuming to use, it highlights the well-documented association between ongoing joint inflammation and progressive radiographic and clinical damage.

Enthesitis

The Leeds Enthesitis Index (LEI), which was developed specifically to assess PsA, is one of the most frequently used instruments to evaluate clinical enthesitis. In addition, the Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score (MASES) and the Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada Enthesitis Index (SPARCC) may also be used.

The LEI score only utilizes six sites for assessment and includes the bilateral Achilles insertions, medial femoral condyles, and lateral epicondyles of the humerus.

The main points to be aware of in clinical practice when assessing enthesitis include

- the lack of correlation between radiographic imaging of enthesitis and clinical presentation;

- and the importance of differentiating coexistent fibromyalgia and entheseal tenderness.

Dactylitis

A modification of the Leeds Dactylitis Index (LDI) is used to assess dactylitis. The basic LDI requires assessment of digit tenderness (0 = not tender and 1 = tender) by applying pressure (enough to blanch the examiner’s nailbed), along with the use of a circumferometer to measure the circumference of the base of the digit.

A dactylitic digit may be painful (hot dactylitis) or asymptomatic (cold dactylitis). Hot dactylitis may be accompanied by tenosynovitis, soft tissue edema, and subcutaneous power Doppler signal compared with cold dactylitis, which may be more associated with synovitis at the joint.

Axial PsA

The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) and Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) are typically used to assess axial PsA despite these scores having only been validated in patients who meet the modified New York Criteria for ankylosing spondylitis.

These instruments assess peripheral joint pain and edema, along with questions on morning stiffness, and therefore may fail to discriminate axial and peripheral activity. While other instruments exist, their value is uncertain while a clear definition of axial PsA remains undetermined.

It is important to note that in the clinic, patients who show axial involvement on imaging may be asymptomatic and lack the expected inflammatory back pain.

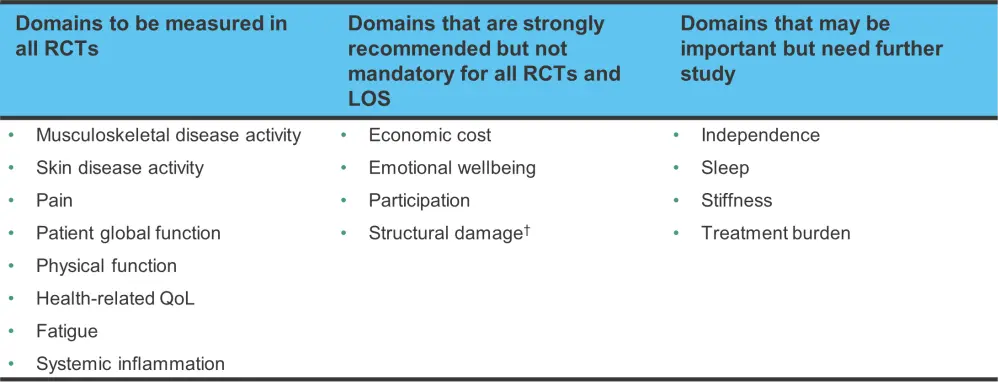

Psoriatic onychodystrophy and psoriasis

A range of instruments are used to assess psoriasis and psoriatic onychodystrophy and a summary can be found in Figure 3. In addition to these, the Psoriasis Symptom Inventory and the Dermatology Quality of Life Index (DLQI), which incorporate patient-reported outcome measures, may also be used. The Physician and Patient Global Assessment of Psoriasis and the Patient and Physician Nail Visual Activity Scales (VAS) may be preferable in practice for ease of use.

Figure 3. Physician-administered instruments used for the assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic nail disease*

BSA, Body Surface Area; DLQI, Dermatology Quality of Life Index; mNAPSI, Modified Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; NAPSI, Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PGA, Physician Global Assessment; PGASkin, PGA Skin; PhNVAS, Physician Nail Visual Activity Scale; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; PtNVAS, Patient Nail Visual Activity Scale; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SNAPS, Severity of Nail Psoriasis Score.

*Adapted from Antony and Tillett.1

Fatigue, pain, QoL, and function assessments

The core domain set for PsA includes global functioning, pain, health-related QoL, and fatigue in patients (Figure 2).

- Pain is often assessed using a VAS or a numeric rating scale.

- QoL is frequently measured with an instrument like the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) or a disease specific instrument, such as the Psoriatic Arthritis Impact of Disease 12-Item Questionnaire (PsAID12).

OMERACT endorses the use of the Health Assessment Questionnaire – Disability Index (HAQ-DI) and the physical function scale of the SF-36 (SF-36 PF) to measure physical function in PsA. In addition, the PsAID12 has been validated and endorsed by OMERACT as a core instrument for the assessment of QoL in PsA.

Composite measures of disease activity

Within the first 2 years of diagnosis, ~50% of patients develop erosive disease and this damage accumulates as the disease progresses. The other half may experience a milder disease course or have only a small number of joints affected. Despite this, PsA can have an impact on par with that of RA in terms of physical function and QoL. The range of disease domains, which may be impacted, such as psoriasis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and axial disease, may explain why QoL and function is adversely affected despite a milder course. Therefore, focusing solely on joint disease could underestimate the overall burden of disease for patients with PsA.

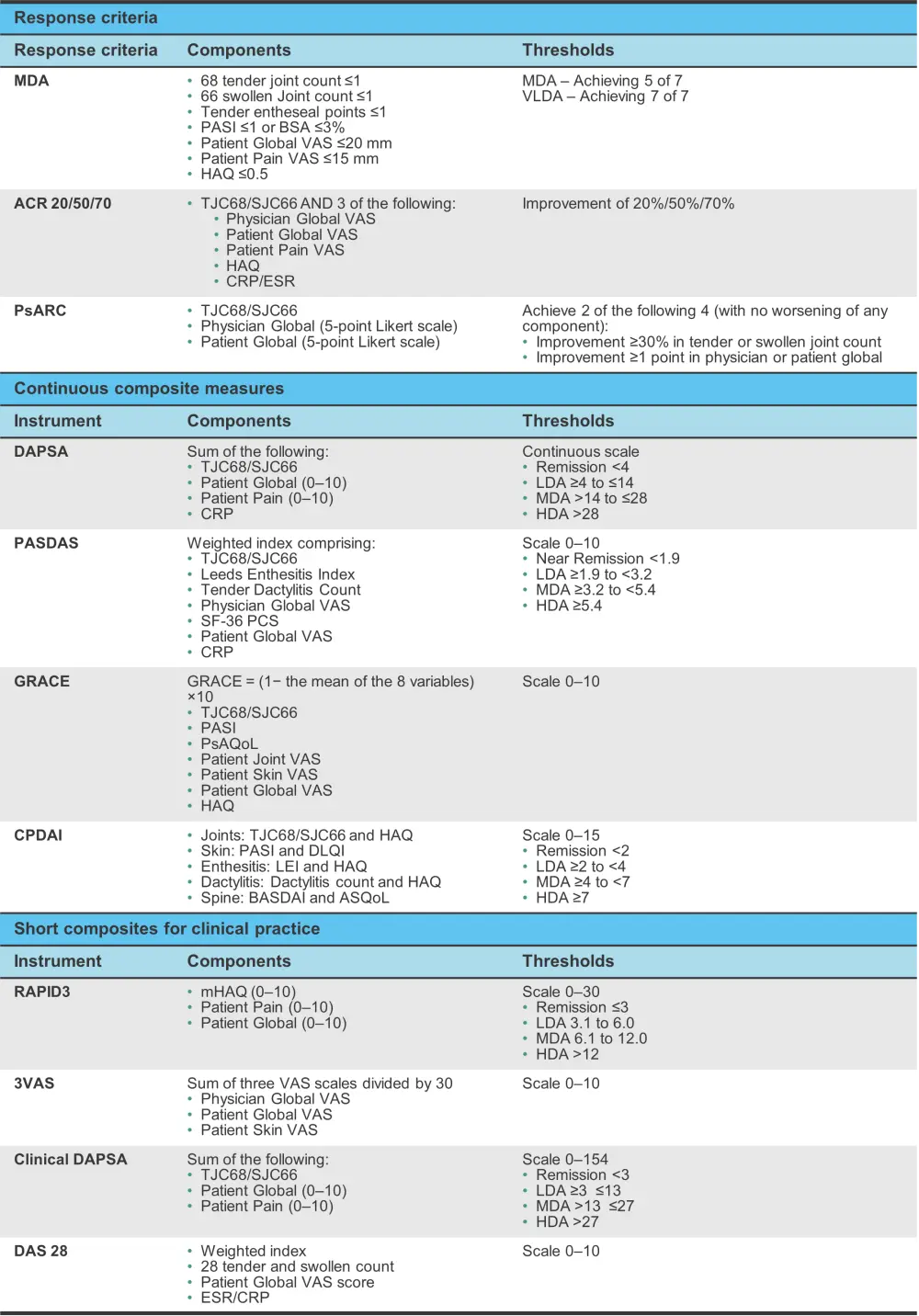

To address this, a composite measure of disease activity is required and the currently used ones are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Composite measures in psoriatic arthritis components and disease activity thresholds*

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; ASQoL, ankylosing spondylitis quality of life; BASDA, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BSA, body surface area; CPDAI, Composite Psoriatic Disease Activity Index; CRP, C-reactive protein; DAPSA, disease activity in psoriatic arthritis; DAS, Disease Activity Score; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HAQ, health assessment questionnaire; HDA, high disease activity; LDA, low disease activity; LEI, Leeds Enthesitis Index; MDA, minimal disease activity; mHAQ, modified HAQ; PASDAS, Psoriatic Arthritis Disease Activity Scale; PASI, Psoriasis Area Severity Index; PsAQoL, psoriatic arthritis quality of life; PsARC, Psoriatic Arthritis Response Criteria; SF-36 PCS, Short Form-36 Physical Component Summary; TJC68/SJC66, 66 swollen and 68 tender joint count; VAS, Visual Activity Scale; VLDA, very low disease activity.

*Adapted from Antony and Tillett.1

Response criteria1

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response criteria, which was developed for RA, is frequently used as the primary endpoint for randomized control trials. It covers 20%, 50%, or 70% improvement in

- joint count;

- physician global;

- patient global;

- patient pain;

- Health Assessment Questionnaire;

- and C-reactive protein (CRP) or erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

However, the ACR response criteria only assesses articular disease. The Psoriatic Arthritis Response Criteria (PsARC) is endorsed by some health agencies; however, it is infrequently used as other instruments show improved discrimination.

To combat these issues, the minimal disease activity (MDA) criteria were developed, which use physician assessment of joints, skin, and enthesitis, patient reported pain, physical function, and global disease activity to evaluate PsA.

While response criteria may be useful, they do not measure changes in disease activity along a scale. Continuous measurement instruments have been developed with validated cut-offs for remission, and low to high disease activity. The Composite Psoriatic Arthritis Disease Activity Index (CPDAI) was designed to assess the OMERACT core domains (Figure 3) and has defined thresholds for disease activity. However, it is not widely used due to a lack of patient outcome measures, such as pain and fatigue, along with a perceived lack of feasibility in the clinic.

Another instrument that was developed for RA initially but has been adapted for PsA is the Disease Activity in Psoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA). This instrument is simple to use and measures articular disease comprising a joint count, patient global and pain scores, and CRP. A clinical version of DAPSA that does not include CRP assessment in the laboratory has also been created for routine practice.

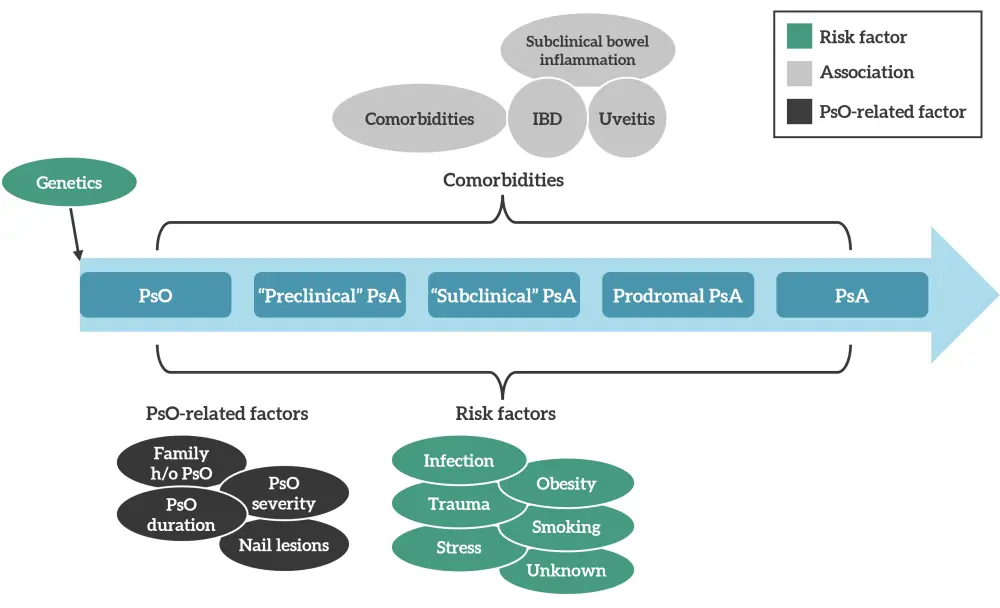

Clinical risk factors2

Approximately 90% of cases of PsA occur in patients with psoriasis. There is a latency period of a few years prior to the onset of PsA, and studies suggest that the development of arthritis is the result of a complex interplay of multiple factors (Figure 5) making it unlikely for a single factor to effectively define patients at risk of PsA.

Figure 5. Interplay of disparate variables in PsA development*

h/o, history of; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; Pso, psoriasis.

*Adapted from Karmacharya, et al.2

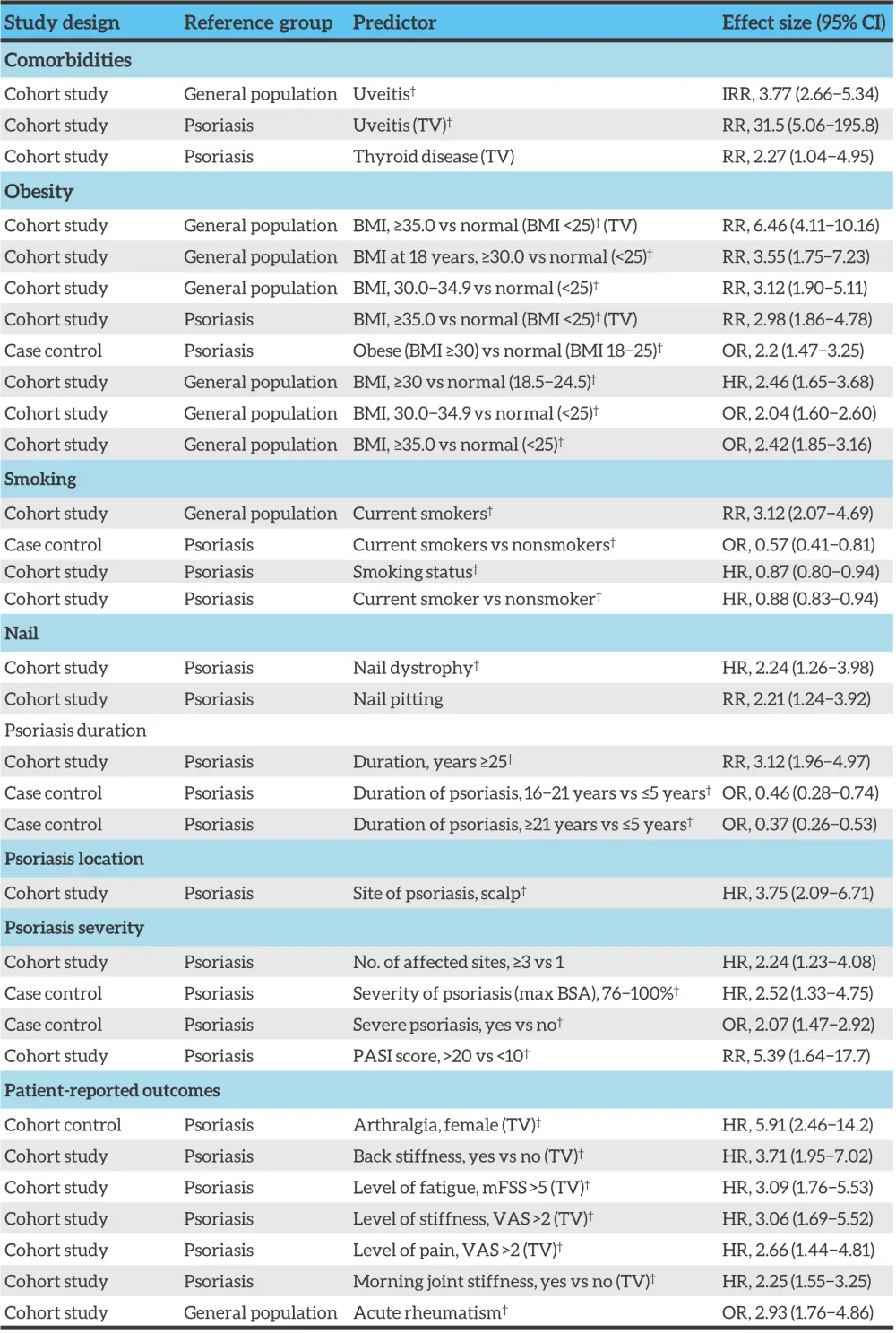

A higher prevalence of severe psoriasis in patients with PsA compared with psoriasis only has been reported by several studies. One study found an association between the number of psoriasis sites and the chance of developing PsA (hazard ratio, 2.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.23−4.08, for PsA in patients with psoriasis and ≥3 affected sites).

Psoriasis of the nail or scalp, and inverse psoriasis have been associated with PsA development. Nail dystrophy is found at an increased prevalence in patients with PsA (41−93%) compared with psoriasis only (15−50%). Nail pitting and onycholysis have also shown to be associated with PsA development (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Clinical risk factors for psoriatic arthritis*

BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IRR, incidence rate ratio, mFSS, modified fatigue severity scale; OR, odds ratio; PASI, psoriasis area and severity index; RR, relative risk; TV, time varying exposure; VAS, visual analogue scale.

*Adapted from Karmacharya, et al.2

†Indicates adjustment for other covariates.

An association has also been highlighted between body mass index and risk of PsA development. Multiple studies show a BMI >30 is associated with relative risk >2.

Uveitis risk appears to be increased in patients with PsA (incidence rate [IR], 3.77; 95% CI, 2.66−5.34) compared with psoriasis alone (IR for mild psoriasis, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.32−1.91; and IR for severe psoriasis, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.40−3.38).

Conclusion

With respect to classification of PsA, the validation of the CASPAR criteria is a step forward in the pursuit of a uniform classification system. While there are many classification systems, there are some key unmet needs remaining, such as the lack of definition of axial PsA and the need for composite outcome measures use in randomized control trials and longitudinal observational studies. There is no single risk factor that defines which patients are at risk for developing PsA, rather a complex interplay of different factors appear to be at work in the development of PsA. Focusing on modifiable risk factors, such as smoking and obesity, may improve outcomes and reduce the risk of PsA development.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with plaque psoriasis do you see per month?