All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The pso Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the pso Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The pso and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The PsOPsA Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported by educational grants. We would like to express our gratitude to the following companies for their support: UCB, founding supporter. The funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis content recommended for you

Small-molecule systemic oral therapies for psoriasis and PsA

Do you know... Which of the following drugs is an example of a tyrosine kinase inhibitor?

There are different types of medications for psoriatic disease which include topical, oral, biologic agents, and phototherapies.1 Patients with mild-to-moderate psoriasis are often treated with topical medication or phototherapy, with systemic therapies utilized in patients with moderate-to-severe disease.1 However, there can be variability in treatment response, and patients may have preferences for treatment type.2

Here, we focus on small-molecule systemic oral therapies for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA), providing a comprehensive overview of their efficacy, safety, and place in the treatment landscape. We provide expert opinions from Laura Coates and Paolo Gisondi at the end of this article.

Overview of oral therapies

Oral systemic therapies are often used in patients who do not yield a response to topical or ultraviolet light therapies, or who have a preference for oral therapy.3

Examples of conventional oral therapies include:

-

cyclosporine;

-

methotrexate;

-

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; and

-

acitretin.

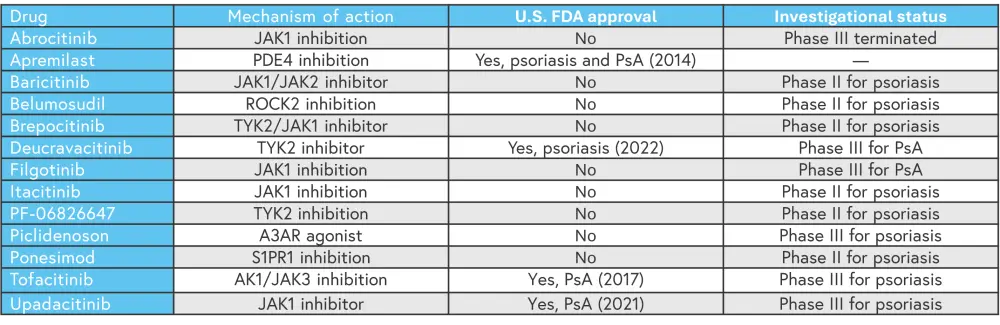

Cyclosporine, methotrexate, and acitretin are standard non-biologic treatments for psoriasis; however, these treatments are not well tolerated with an increased risk for short- and long-term adverse events (AEs).5 Therefore, in recent years there have been an increasing number of novel oral therapies developed for psoriasis which target small molecules found in the inflammatory pathways (Table 1).5

Table 1. Overview of novel oral treatments for psoriasis and PsA*

AK1, adenylate kinase 1; A3AR, A3 adenosine receptor; JAK, Janus kinase; PDE4, phosphodiesterase 4; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; ROCK2, rho-associated kinase 2; S1PR1, sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1; TYK2, tyrosine kinase 2; U.S. FDA, United States Food and Drug Administration.

*Adapted from Marushchak, et al.5

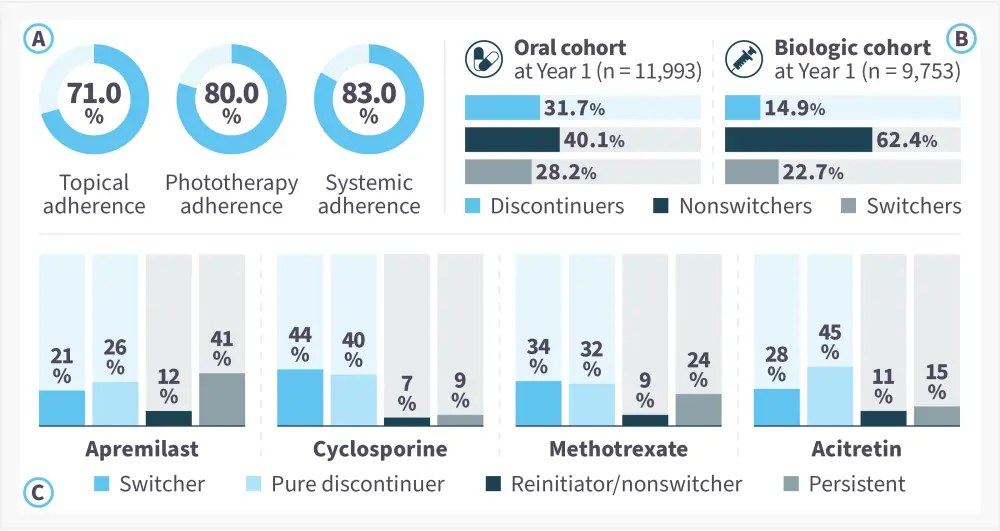

Adherence and treatment patterns

Adherence to psoriasis treatment is an ongoing problem.2 An estimated 40% of patients with psoriasis do not adhere to treatment as prescribed, which can lead to poor outcomes.2 Even in patients who initially adhere to treatment, this adherence may not persist long-term.1 A systematic review of adherence in psoriasis identified that patients on systemic therapy were most likely to adhere to treatment for the duration of their therapy, compared with those receiving topical medication or phototherapy (Figure 1a).6 When comparing oral and biologic treatments, a retrospective cohort study conducted on data from 2006–2019, found that there were higher proportions of patients switching or discontinuing treatment in the oral cohort (Figure 1B), with the greatest switching seen in patients receiving cyclosporine (Figure 1C).1 When comparing apremilast with standard non-biologic oral therapies, persistent adherence was higher (41% vs an average of 16%). Newer safe, effective targeted oral options may therefore further increase adherence among patients with psoriasis.

Figure 1. A Adherence rates (duration of therapy) for different treatment types,6 B switching patterns at 1 year in patients receiving oral and biologic therapy,1 and C treatment patterns at 1 year in patients receiving different oral treatments1*

*Adapted from Thai, et al.1 and Thorneloe, et al.6

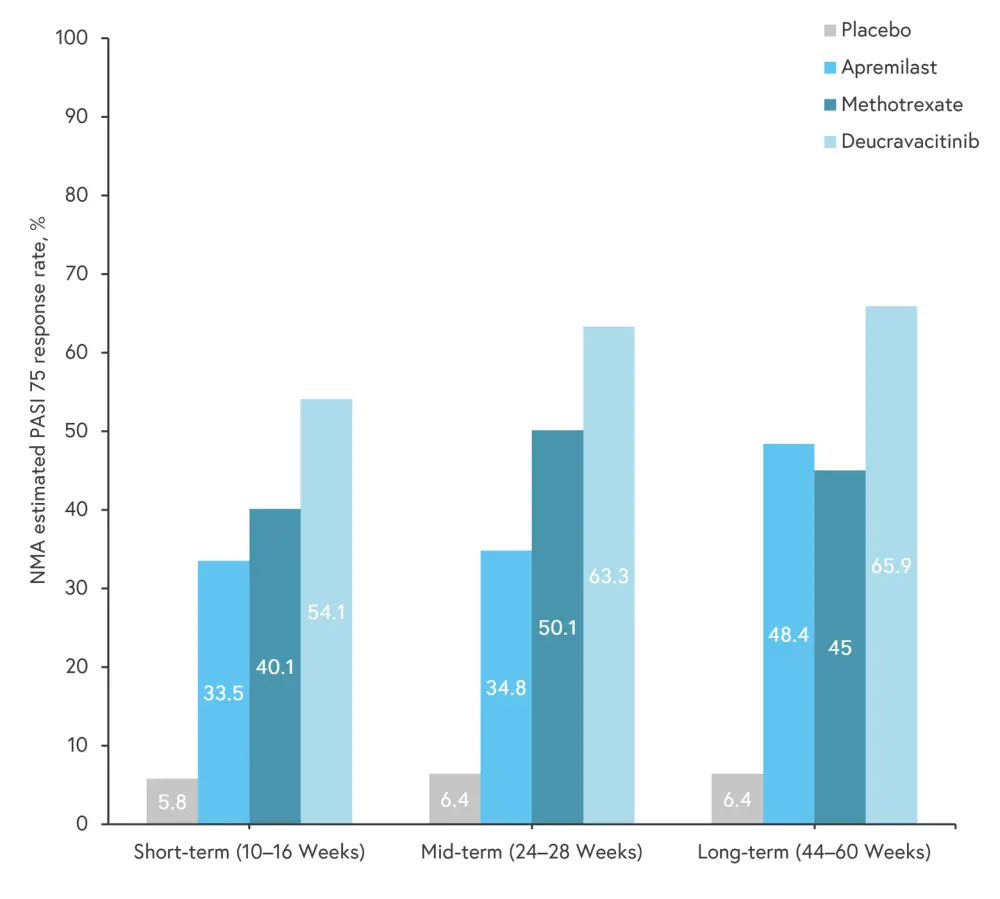

Efficacy of small-molecule oral treatments4

There are several small molecule oral treatments which already have proven efficacy and have been approved in psoriatic disease, including deucravacitinib, tofacitinib, and upadacitinib. There are more treatments which are currently in phase III trials for psoriasis and PsA and may be approved in the future (Table 1). While comparative data for oral treatments are limited, a network meta-analysis by Sbidian et al.,7 showed that there was no significant difference between tofacitinib or apremilast compared with ciclosporin and methotrexate in achieving Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 90 (assessed from 8–24 weeks after randomization).7 Another network meta-analysis by Armstrong et al.,4 indirectly compared deucravacitinib with non-biologic oral treatments, and first- and second-generation biologics. The meta-analysis included 47 phase III trials in adult patients with plaque psoriasis, which assessed improvements in PASI from baseline. Compared with non-biologic oral treatments, deucravacitinib showed the highest rate of 75% improvement in PASI (PASI 75) at short-, mid- and long-term follow-up (Figure 2). All the oral treatments had a higher PASI 75 response rate compared with placebo, with deucravacitinib achieving the highest PASI 75 at all-time points amongst the oral treatments.

Figure 2. PASI 75 rates at different time points for oral treatments*

NMA, network meta-analysis; PASI 75, 75% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index.

*Adapted from Armstrong, et al.4

Safety of small-molecule oral treatments

The commonly used oral therapies in psoriasis, such as methotrexate, cyclosporine, and acitretin, have an increased risk of short- and long-term AEs, leading to the development of new small-molecule oral therapies, which are less likely to have off-target effects.5 However, AEs vary between treatments. Some biologics have been associated with a higher risk of infections with long-term use, and tofacitinib and upadacitinib have boxed warnings for serious infections stated on their U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) prescribing information resources.8 Higher selectivity may reduce AEs, and deucravacitinib, as a potent and selective tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor (TYK2) has no boxed warnings.5 A pooled analysis found that rates of discontinuation due to AEs reported in clinical trials with tofacitinib and upadacitinib, were generally comparable with rates observed with apremilast.8 A separate analysis of the POETYK phase III trials found that deucravacitinib had the lowest discontinuation rates due to AEs at both 16 and 52 weeks compared with apremilast and placebo.9 Serious AEs occurred at low and similar rates among the deucravacitinib, placebo, and apremilast groups through 1 year of treatment.9

Expert Opinion

-

Janus kinase inhibitors are the only oral effective option for axial spondylarthritis, so for those with axial PsA, this is an important therapeutic option.

-

Interesting data with apremilast has emerged from the FOREMOST study in 2023 (data not yet published). This was the first large study specifically in the oligoarthritis population (<5 joints involved) and showed a significant benefit of apremilast over placebo. This is key as there are very few studies in this subgroup, and the data from patients in this study are interesting for further investigation of oligoarthritis.

Laura Coates

Laura CoatesExpert Opinion

-

Oral small-molecule systemic therapies play a significant role in the treatment of psoriasis, particularly for moderate-to-severe cases where topical treatments and/or phototherapy may not be sufficient. These therapies are designed to target specific pathways involved in the immune response and inflammation associated with psoriasis.

-

Deucravacitinib is a first-in-class TYK2 inhibitor recently approved for the treatment of adults with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. By inhibiting TYK2, deucravacitinib interferes with signaling of interleukin (IL)-23, IL-12, and type I interferons, with cytokines playing important roles in psoriasis pathogenesis.

-

The fact that small molecules interfere with the signaling of multiple cytokines represents a major difference compared with biologic drugs, which instead act on a single and selective cytokine (i.e., tumor necrosis factor-alpha, IL-17, IL-12/23, IL-23), and for this reason treatment with biologics can lead to paradoxical skin reactions, such as eczema during treatment with IL-17 inhibitors drugs or paradoxical psoriasis during treatment with tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors.

-

Another relevant difference between oral small-molecule systemic therapies and biologics is represented by oral administration, which could be more appreciated by some patients than intravenous administration, especially when it is the first systemic treatment, after topical therapy.

Paolo Gisondi

Paolo GisondiConclusion

In general, small-molecule oral therapies are better tolerated than standard non-biologic treatments,3 and can offer an alternative for patients who prefer to avoid topical or intravenous treatments.2 Several novel oral therapies have shown efficacy and gained U.S. FDA approval for psoriasis or PsA (apremilast and deucravacitinib, and tofacitinib, apremilast, and upadacitinib, respectively); however, there are many more which have shown efficacy in phase II and III trials and may be approved in the future. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of such agents will be key for directing clinical decisions. It is also important to take patient preferences into account when selecting treatments, as this can improve clinical outcomes by enhancing satisfaction and adherence.2 The development and approval of novel oral therapies will be key in providing convenient, well tolerated, and efficacious treatment options for patients with psoriasis and PsA.

This educational resource is independently supported by Bristol Myers Squibb. All content is developed by SES in collaboration with an expert steering committee; funders are allowed no influence on the content of this resource.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with plaque psoriasis do you see per month?