All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The pso Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the pso Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The pso and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The PsOPsA Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported by educational grants. We would like to express our gratitude to the following companies for their support: UCB, founding supporter. The funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis content recommended for you

Editorial theme | Differential diagnosis of psoriasis versus other common skin conditions

Featured:

Do you know... Red or pink, smooth, well-defined, non-scaly plaques are common in which type of psoriasis?

Psoriasis affects 2–3% of the general population and can affect any part of the body.1 Due its varied clinical features, psoriasis it can be mistaken for other inflammatory, infectious, or neoplastic conditions.1 Differential diagnosis can be difficult and may involve extensive testing to determine the correct diagnosis.1 Here, we discuss how psoriasis may present in various parts of the body and how it can be differentiated from other similar conditions.

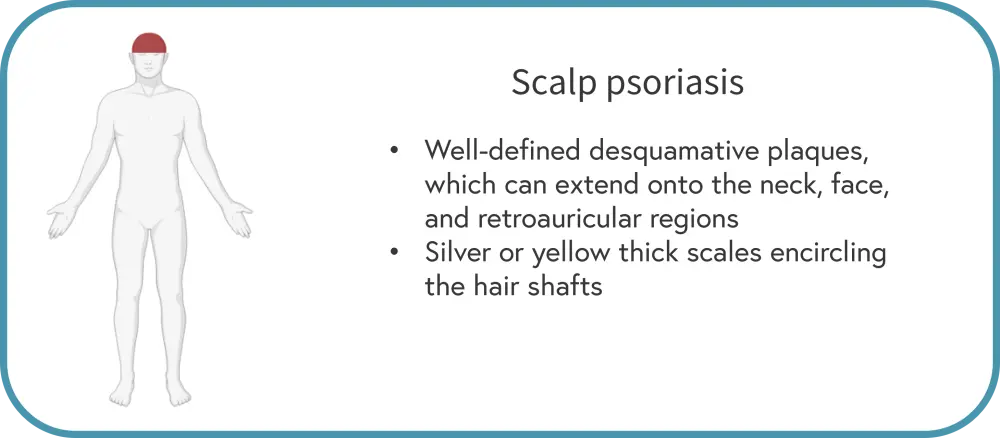

Scalp1

Characteristics of scalp psoriasis are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Clinical characteristics of scalp psoriasis*

*Data from Gisondi, et al.1

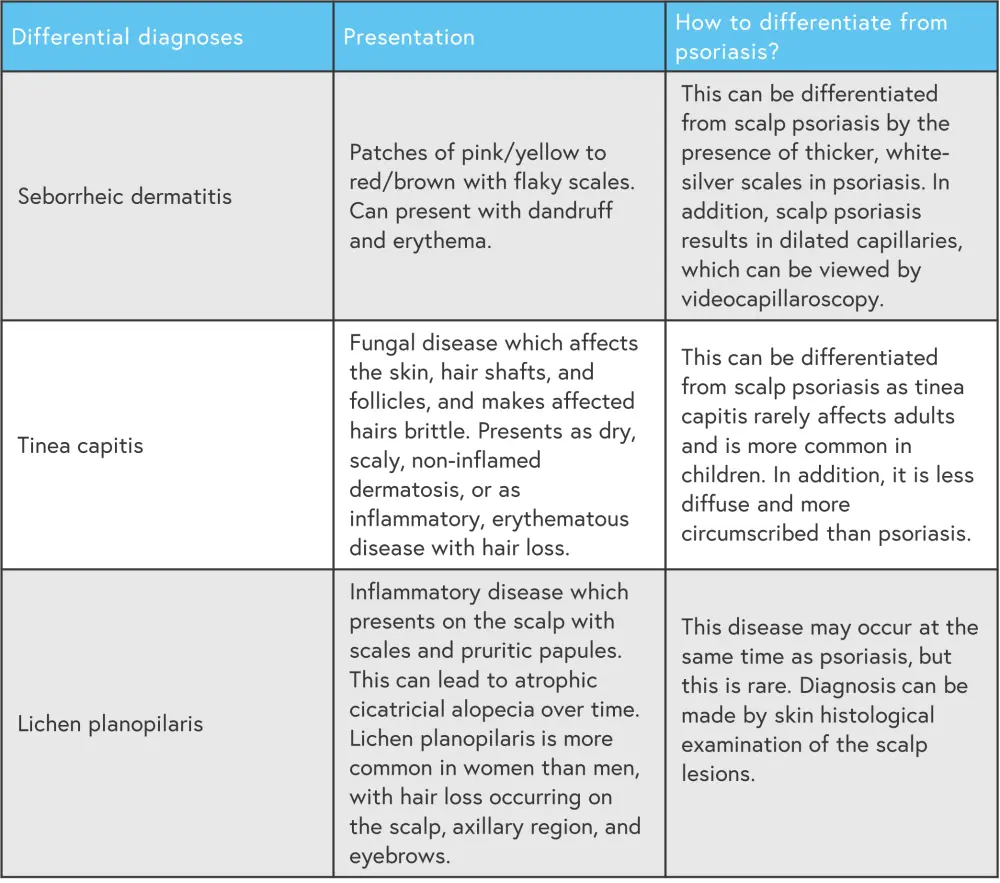

Figure 2. Differential diagnoses for scalp psoriasis*

*Data from Gisondi, et al.1

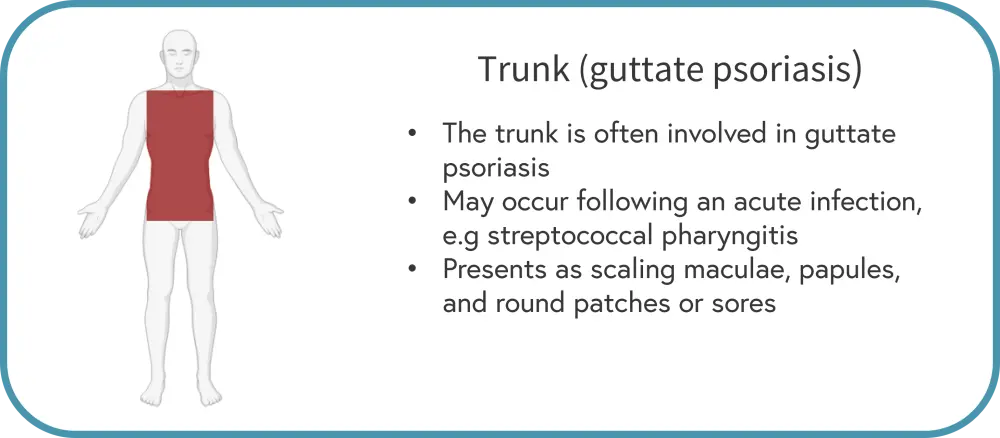

Trunk1

Characteristics of psoriasis of the trunk are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Clinical characteristics of guttate psoriasis of the trunk*

*Data from Gisondi, et al.1

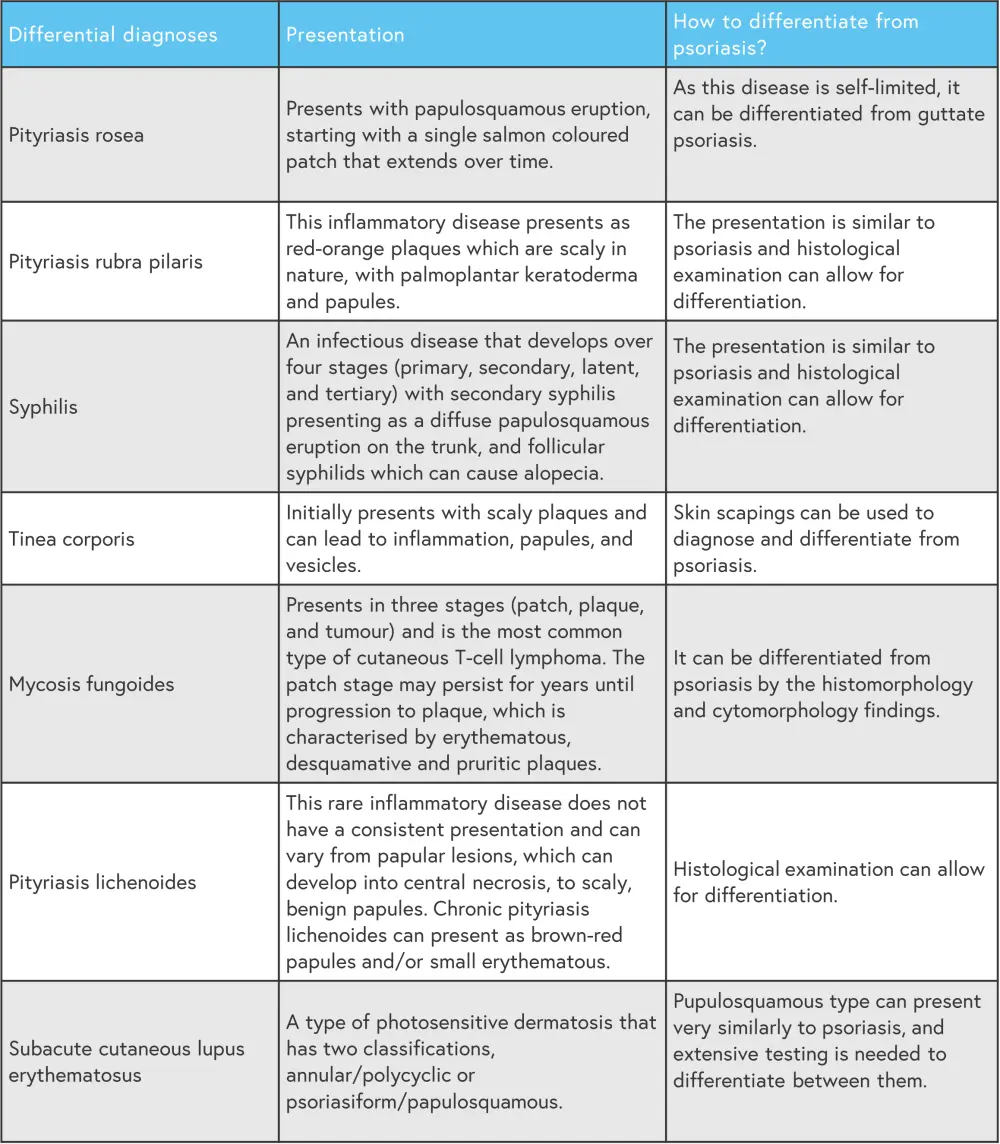

Figure 4. Differential diagnoses for trunk psoriasis*

*Data from Gisondi, et al.1

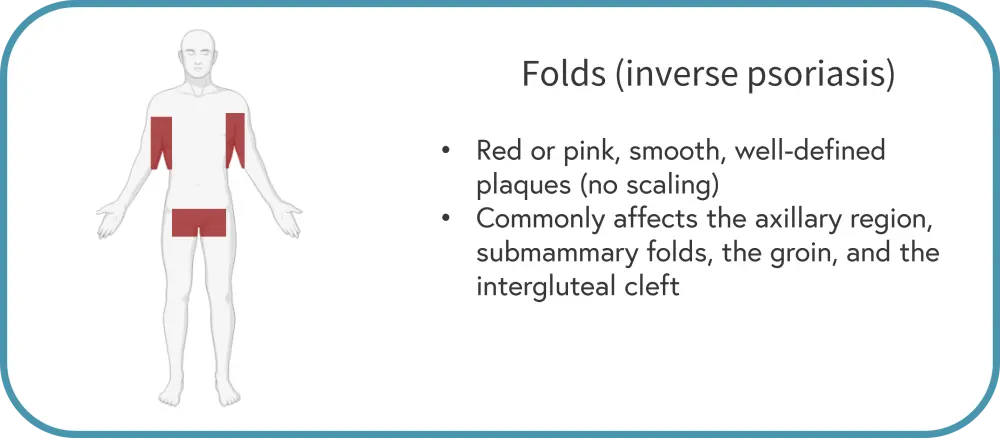

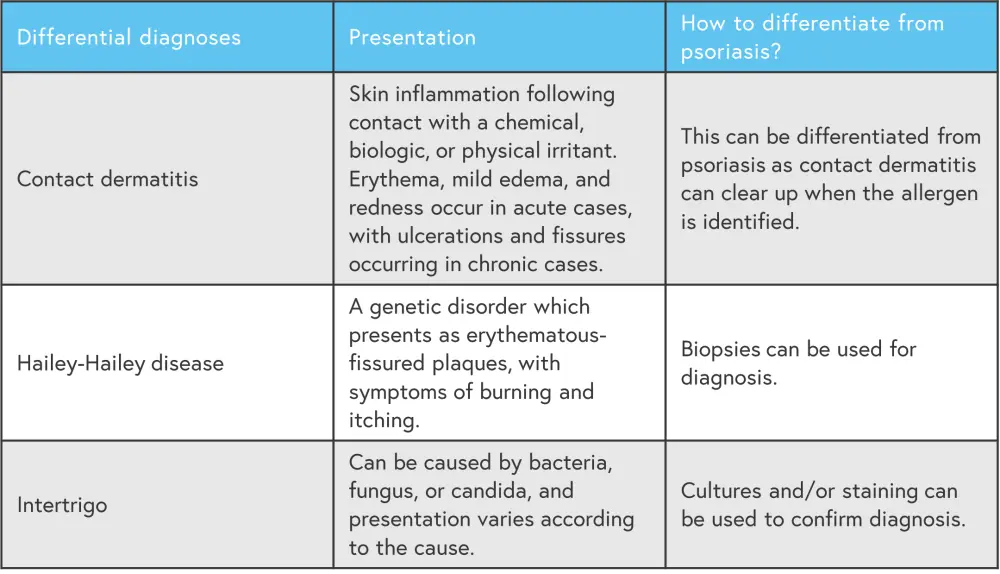

Folds1

Characteristics of psoriasis of the skin folds are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Clinical characteristics of inverse psoriasis of the skin folds*

*Data from Gisondi, et al.1

Figure 6. Differential diagnoses for psoriasis of the folds*

*Data from Gisondi, et al.1

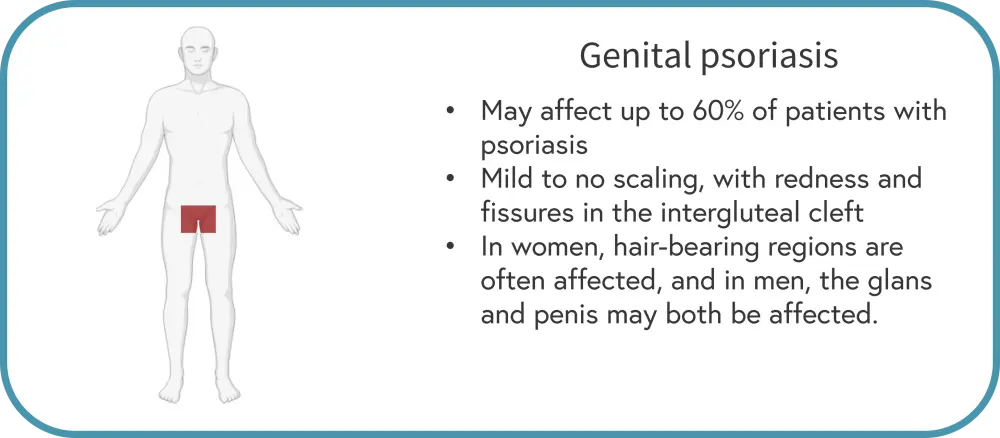

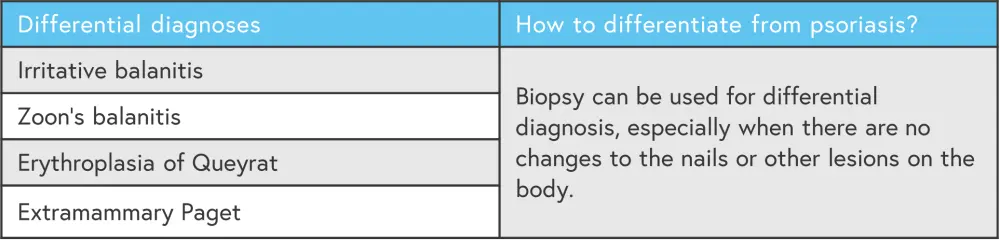

Genitals1

Characteristics of psoriasis of the genitals are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Clinical characteristics of genital psoriasis*

*Data from Gisondi, et al.1

Figure 8. Differential diagnoses for genital psoriasis*

*Data from Gisondi, et al.1

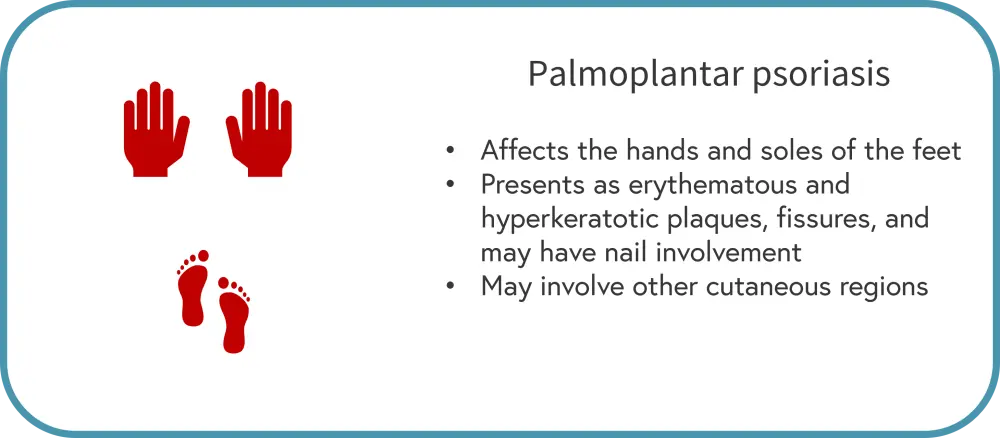

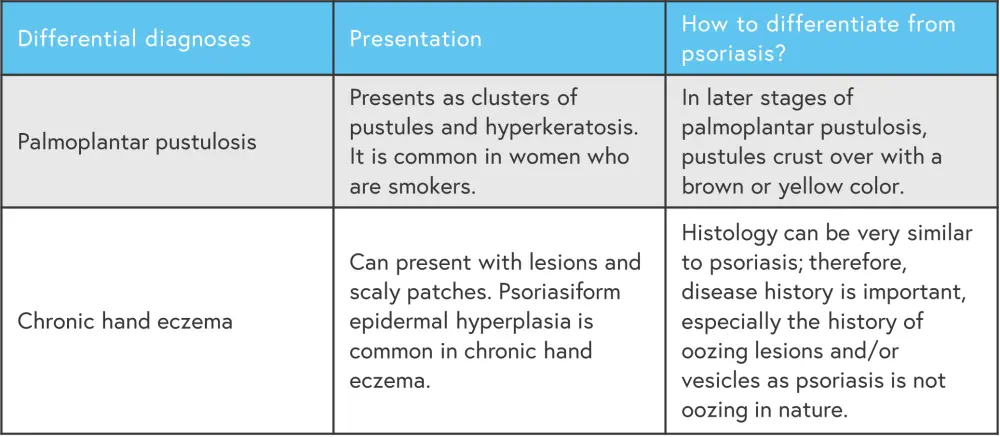

Palms and soles1

Characteristics of palmoplantar psoriasis are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 9. Clinical characteristics of palmoplantar psoriasis*

*Data from Gisondi, et al.1

Figure 10. Differential diagnoses for palmoplantar psoriasis*

*Data from Gisondi, et al.1

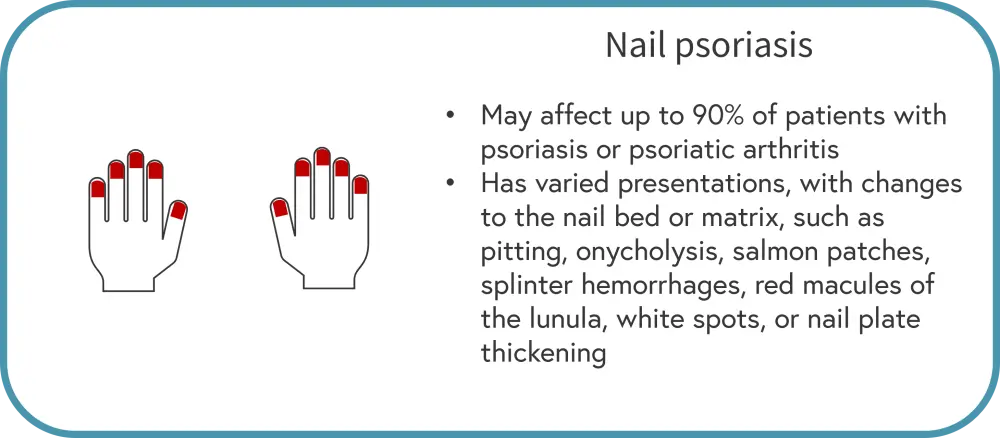

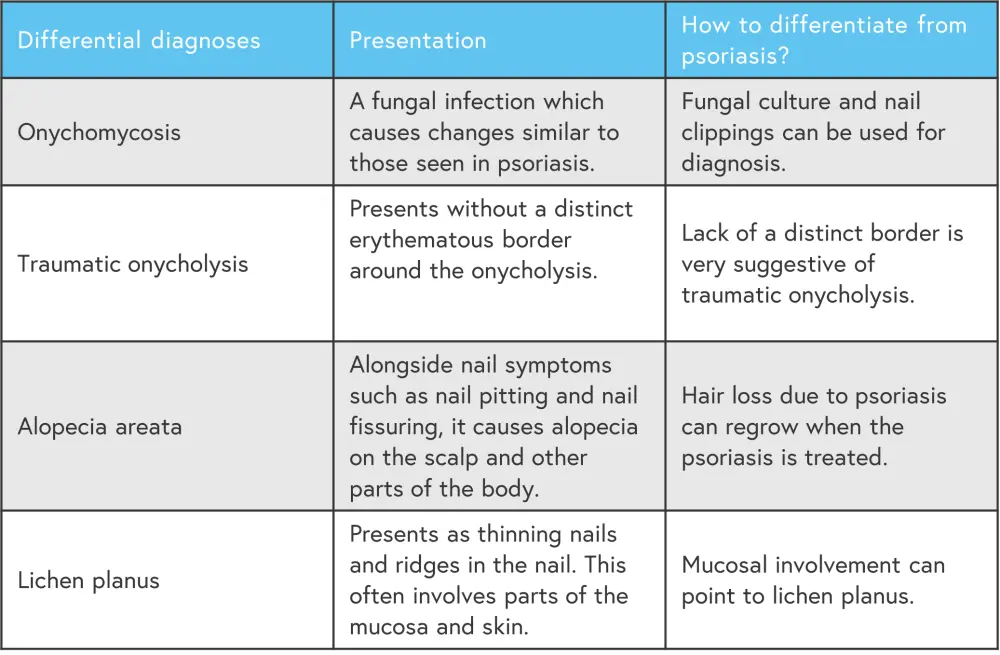

Nails1

Characteristics of nail psoriasis are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Clinical characteristics of nail psoriasis*

*Data from Gisondi, et al.1

Figure 12. Differential diagnoses for nail psoriasis*

*Data from Gisondi, et al.1

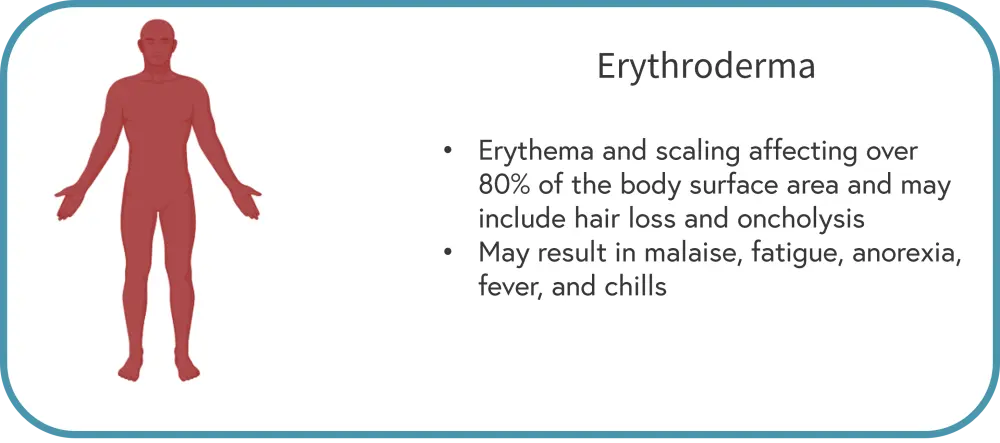

Erythroderma1

Characteristics of erythroderma (due to psoriasis) are shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13. Clinical characteristics of erythroderma*

*Data from Gisondi, et al.1

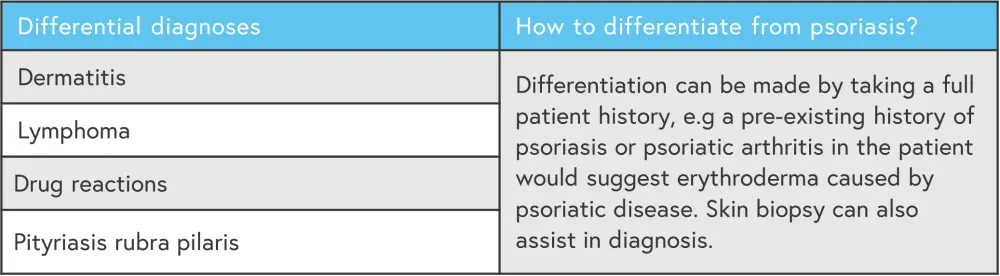

Figure 14. Differential diagnoses for erythroderma*

*Data from Gisondi, et al.1

Conclusion

Considering its wide range of clinical features and presentations, diagnosing psoriasis can be a challenge; similar to other skin diseases.1 A correct psoriasis diagnosis is not only vital for the patient, but also for rheumatologists; psoriatic arthritis also occurs in around a third of patients with psoriasis.1

Expert opinion

The basic message of the article can be summarized thus: "not everything that is red and that scales is psoriasis…"

The meaning

I mean that the diagnosis of psoriasis is usually straightforward for a dermatologist, but may be at times challenging because some the clinical features resemble other common skin disorders including seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, mycosis, lichen planus, syphilis, and less common conditions, including lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, cutaneous T-cell lymphomas, pityriasis rubra pilaris. Diagnostic doubts may also arise when psoriasis coexists with other skin diseases, such as atopic dermatitis in the same patient.

The article provides a pragmatic guide in the differential diagnosis based on a topographical criterion, i.e., based on the localization of the lesions.

What to do if you have a diagnostic doubt?

Punch biopsy represents the gold standard for most differential diagnosis, apart from nail psoriasis. Skin histopathology shows a psoriasiform reaction pattern, defined as the presence of epidermal hyperplasia with a regular elongation of the rete ridges with bulbous enlargement of their tips. Dermal papillae contain dilated, congested, and tortuous capillaries.

The infiltrate is superficial, perivascular, lymphocytic and neutrophilic. Parakeratosis is initially focal and later confluent, containing typical collections of neutrophils (Munro’s microabscesses).

Any alternative to biopsy?

However, before skin biopsy, dermoscopy is an interesting, helpful, and moreover non-invasive procedure. In case of psoriasis, it shows red dots or globules in a regular distribution on a light red or pink background covered with white scales. The vascular features appear as bushy (glomerular) vessels.

Final comment

Differential diagnosis in dermatology is a fascinating daily challenge that is fundamental in clinical practice, because you only recognize what you know. It is a critical step before prescribing any therapy.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with plaque psoriasis do you see per month?

Paolo Gisondi

Paolo Gisondi