All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The pso Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the pso Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The pso and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The PsOPsA Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported by educational grants. We would like to express our gratitude to the following companies for their support: UCB, founding supporter. The funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis content recommended for you

The pathogenesis and management of rare types of psoriasis

Do you know... Which of the following alleles is strongly linked to the onset of guttate psoriasis?

Psoriasis affects approximately 2% of the global population,1,3 with plaque psoriasis making up ~90% of all cases.2 Rarer types of psoriasis include pustular psoriasis, erythrodermic psoriasis, and guttate psoriasis.

- Generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP), which can be life threatening, is characterized by a rash, grouped sterile pustules, and systemic flushing. The global incidence of GPP is unclear; however, it affects approximately 0.0001% of the population, with variation between countries, and is more prevalent in women than men. Also, over half of patients with GPP have previously been diagnosed with plaque psoriasis.2

- Erythrodermic psoriasis (EP) makes up approximately 1–2.25% of all psoriasis cases and is characterized by inflammatory erythema covering ≥75% of the body surface area, although some clinicians argue that ≥90% of the body surface area should be affected for an EP diagnosis.1

- Guttate psoriasis is often triggered by a streptococcal infection or an upper respiratory tract infection, although there are other possible triggers. Guttate psoriasis presents as small lesions and is more common in children than adults.3

Guidance for the management and treatment of these rarer psoriasis types is limited. Below, we discuss the pathogenesis and management of pustular, erythrodermic, and guttate psoriasis.

Pathogenesis

GPP2

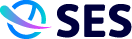

The pathogenesis of GPP often involves a loss of function mutation in the IL36RN gene, which encodes an interleukin (IL)-36R antagonist; this leads to a cytokine storm due to the lack of IL-36R regulation and further activates pro-inflammatory cytokines. In patients diagnosed with GPP, there is often a family history of psoriasis, with prevalence of the IL36RN mutation varying across ethnicities and between those with or without plaque psoriasis. GPP pathogenesis can involve other mutations (CARD14 gain of function, MPO deficiency, and AP1S3 loss of function) that further activate the IL-36 pathway. The pathogenesis of GPP is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1. GPP pathogenesis*

AP1S3, adaptor related protein complex 1 subunit sigma 3; CARD14, caspase recruitment domain family member 14; GOF, gain of function; GPP, generalized pustular psoriasis; IL, interleukin; IL-36Ra, interleukin 36 receptor antagonist; LOF, loss of function; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MPO, myeloperoxidase; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B.

*Adapted from Kodali, et al.2 Created with BioRender.com

EP1

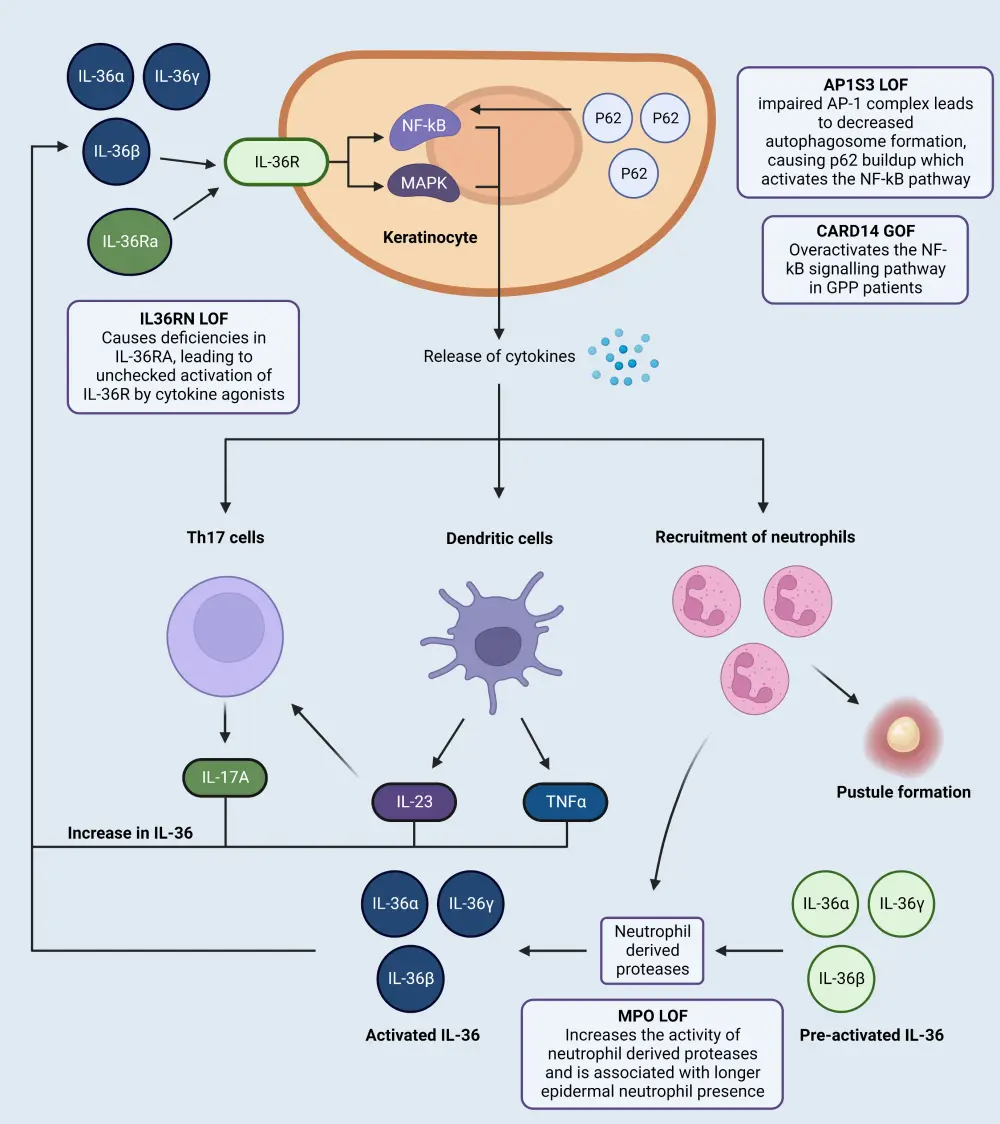

The pathogenesis of EP has not yet been fully elucidated; however, in a recent retrospective study, a lower ratio of Th1/Th2 cells and higher IL-4 and IL-10 levels were seen in EP compared with plaque psoriasis and healthy controls. Most studies investigating the pathogenesis of EP suggest an association with the Th2 phenotype. In addition, immunosuppression seen in patients with EP may be due to plasma intracellular adhesion molecules. Several biomarkers implicated in EP are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Biomarkers in EP*

EP, erythrodermic psoriasis; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; Th, T helper cell; MIP, macrophage inflammatory protein.

*Adapted from Singh, et al.1

Guttate psoriasis3

The PSORS1 gene, which contains the HLA-Cw6 allele, is implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis, while the HLA B-13 and HLA B-17 alleles have been strongly linked to the onset of guttate psoriasis.

Management

GPP2

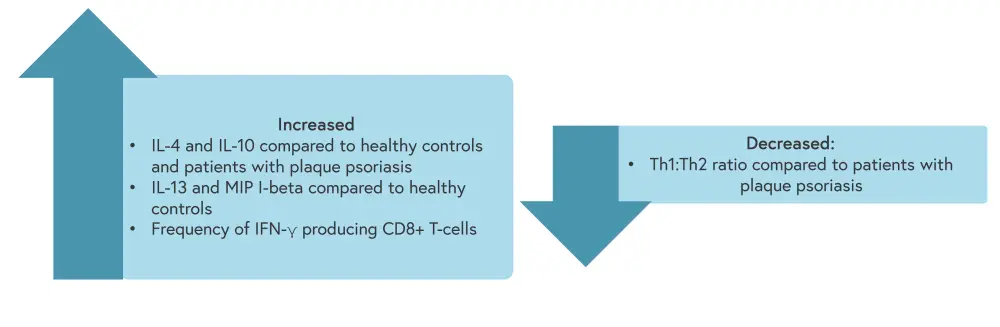

Access to first-line treatment options for GPP varies between countries. Currently, just one GPP-specific treatment, spesolimab, is U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) approved. However, the long-term safety and efficacy of spesolimab is not clear, with trials currently ongoing. Biologics are also approved in the United States, Japan, Thailand, and Taiwan for the treatment of GPP. A list of common GPP treatments is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. GPP treatment options*

GPP, generalized pustular psoriasis; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

*Adapted from Kodali, et al.2

Topical therapies, such as calamine, can also be utilized alongside systemic treatment to decrease skin irritation and reduce pustules.

EP1

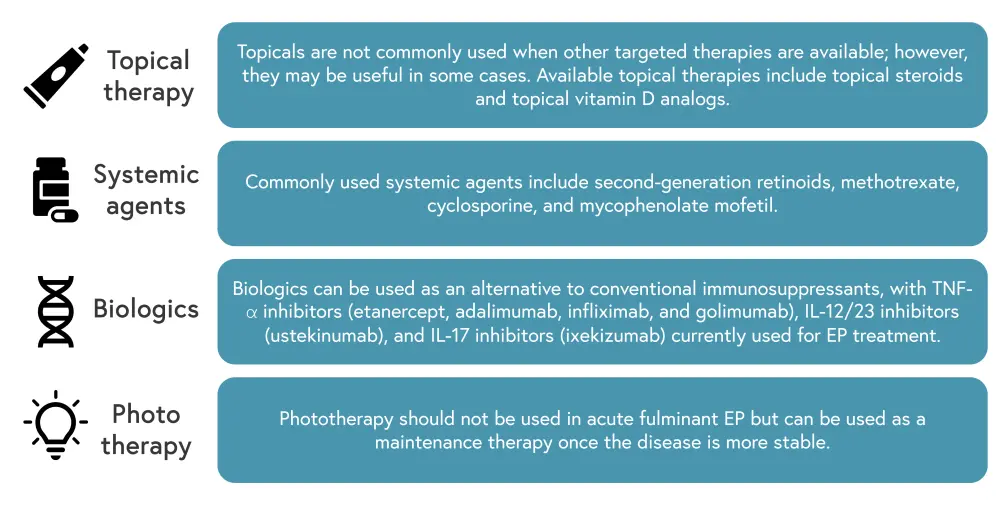

EP treatment should be based on the patient’s disease presentation and will often require supportive therapies, such as the administration of fluids, nutritional assessments, and hypothermia prophylaxis. In addition, EP should be monitored for the development of sepsis, which can be fatal. Common treatments used in patients with EP are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. EP treatment options*

EP, erythrodermic psoriasis; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

*Adapted from Singh, et al.1

Guidelines for first-line EP treatment in the United States depend on disease severity. Acitretin and methotrexate are recommended for stable EP cases, while cyclosporine or infliximab are recommended for unstable or acute cases. Recent studies also suggest that ustekinumab can be an effective treatment for stable EP. Currently, calcipotriol and calcitriol are not advised for use in patients with severe EP, while teratogens such as retinoids and mycophenolate mofetil should be used with caution.

Guttate psoriasis3

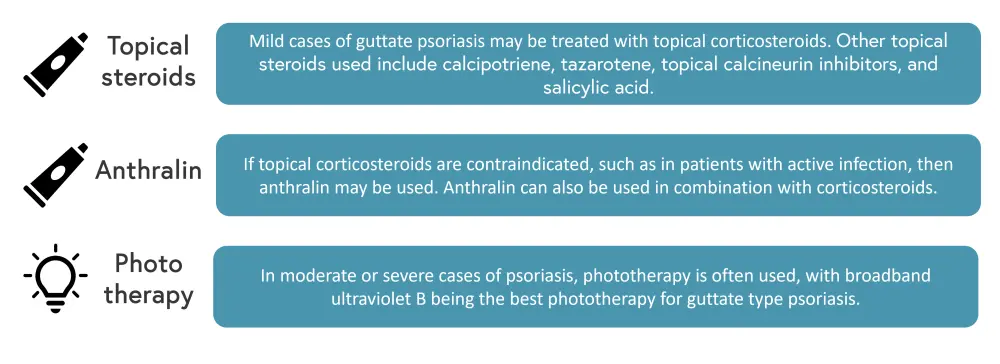

The treatment of guttate psoriasis is also based on the severity of disease presentation. Biologics have not been investigated in guttate psoriasis and are not currently recommended, unless there is progression to plaque psoriasis. Most patients will fully recover from guttate psoriasis; however, approximately 40% of patients will progress to plaque psoriasis. An overview of treatments for guttate psoriasis is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Guttate psoriasis treatment options*

*Adapted from Saleh, et al.3

Conclusion

The management of GPP aims to clear skin symptoms and reduce the risk of disfigurement and distress to patients.2 Spesolimab is an effective treatment for acute GPP; however, more data is required to fully understand its potential in chronic cases or flare prevention.2 Additional studies, comparing the efficacy and safety of biologic treatments, could lead to the approval of additional treatments for GPP in the United States, leading to more effective treatment guidelines. In both EP and guttate psoriasis, additional studies to evaluate the long-term safety and efficacy of treatments, especially biologics, as well as the disease pathogenesis would be beneficial to aid the development of treatment guidelines.1,3

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with plaque psoriasis do you see per month?