All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The pso Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the pso Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The pso and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The PsOPsA Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported by educational grants. We would like to express our gratitude to the following companies for their support: UCB, founding supporter. The funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis content recommended for you

Phase III KEEPsAKE-1 trial: Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis

Do you know... Which of the following statements describing the safety profile of risankizumab vs placebo in the KEEPsAKE-1 trial is true?

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic multifaceted inflammatory disease that often occurs in combination with psoriasis.1 PsA has diverse clinical manifestations, which may include arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, axial involvement, and skin and/or nail involvement. PsA impacts patients both physically (pain and fatigue) and psychologically (emotional wellbeing), leading to a poor quality of life. To improve quality of life in patients with PsA, the treatment of all facets of PsA is essential. Although there are a range of PsA therapies (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, local corticosteroid injections, and conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs [csDMARDs]), biological therapies are utilized for patients who have poor prognostic factors or who do not respond to frontline treatments.1

Risankizumab is a monoclonal antibody that blocks the action of interleukin-23 to treat moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis.1 Recently, risankizumab has been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA),2 Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in the UK,3 and the European Medicines Agency (EMA)4 for the treatment of adults with PsA. These approvals were based on results of the phase III KEEPsAKE-1 (NCT03675308) and KEEPsAKE-2 (NCT03671148) trials. The KEEPsAKE-1 trial is evaluating the effectiveness and safety of risankizumab in the treatment of PsA in patients with inadequate response or intolerance to available therapies.1 Here we summarize the recently published results from the first 24 weeks of the KEEPsAKE-1 trial.

Study design

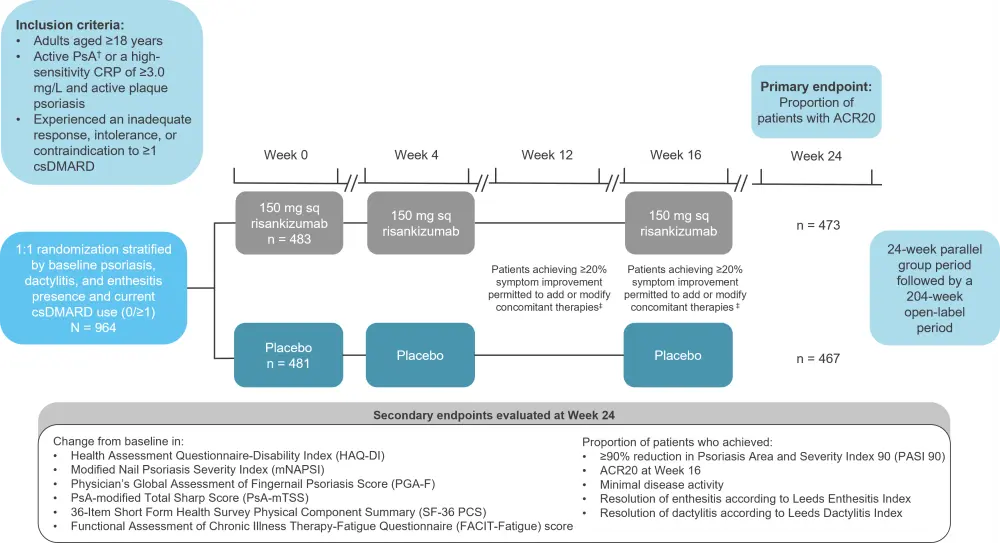

The KEEPsAKE-1 trial is a phase III, global, multicenter trial in adult patients consisting of a 24-week double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group period, during which safety and adverse event monitoring was measured throughout, as well as a 204-week open-label period to evaluate long-term efficacy and safety (Figure 1).

Figure 1. KEEPsAKE-1 trial design*

ACR20, 20% improvement in American College of Rheumatology score; CRP, C-reactive protein; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; sq, subcutaneous.

*Adapted from Kristensen, et al.1

†Symptom onset ≥6 months, meeting the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis, ≥5 of 68 tender and joints, ≥5 of 66 swollen joints, and ≥1 erosion in hands and/or feet based on a centrally read radiograph.

‡Improvement based on swollen and/or tender joint count.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 940 patients completed the study between March 2019 and October 2020 (Figure 1). Most patients were considered to have an inadequate response (85.2%), intolerance (14.4%), or contraindication (0.4%) to prior therapy with ≥1 csDMARD. The baseline characteristics were generally well balanced between the two groups, including the proportion of patients using concomitant csDMARDs (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics*

|

BMI, body mass index; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; FACIT-Fatigue, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; LDI, Leeds Dactylitis Index; LEI, Leeds Enthesitis Index; MDA, minimal disease activity for PsA; mNAPSI, modified Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; MTX, methotrexate; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PGA-F, Physician’s Global Assessment of Fingernail Psoriasis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; PsA-mTSS, PsA-modified Total Sharp Score; SD, standard deviation. |

||

|

Characteristic |

Risankizumab 150 mg |

Placebo |

|---|---|---|

|

Median age (range), years |

52 (20–85) |

52 (22–79) |

|

Female, % |

47.8 |

51.4 |

|

Mean BMI, kg/m2 (SD) |

6.4 |

6.2 |

|

Mean PsA duration, years (SD) |

7.1 (7.0) |

7.1 (7.7) |

|

Mean HAQ-DI (SD) |

1.15 (0.66) |

1.17 (0.65) |

|

Mean hsCRP, mg/L (SD) |

11.9 (15.9) |

11.3 (14.1) |

|

Mean PsA-mTSS (SD) |

13.0 (29.9) |

13.5 (29.0) |

|

Presence of nail psoriasis, % |

64.0 |

70.6 |

|

Mean mNAPSI (LEI >0) (SD) |

18.1 (16.4) |

16.6 (16.0) |

|

Mean PGA-F (LEI >0) (SD) |

2.1 (1.0) |

2.0 (1.0) |

|

MDA, % |

0.4 |

1.2 |

|

Presence of enthesitis, %† |

61.5 |

60.3 |

|

Mean LEI (SD) |

2.7 (1.5) |

2.6 (1.5) |

|

Presence of dactylitis, %‡ |

30.6 |

30.6 |

|

Mean LDI (SD) |

98.6 (120.4) |

92.5 (125.5) |

|

Mean FACIT-Fatigue (SD) |

29.4 (11.3) |

29.3 (11.2) |

|

Prior csDMARDs, %§ |

|

|

|

0 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

|

1 |

70.0 |

64.7 |

|

2 |

21.7 |

28.3 |

|

≥3 |

7.9 |

6.7 |

|

Concomitant medication, % |

|

|

|

MTX‖ |

65.0 |

65.5 |

|

csDMARD other than MTX¶ |

10.8 |

10.2 |

|

MTX and another csDMARD |

4.1 |

6.0 |

|

Oral corticosteroids |

20.9 |

18.1 |

|

NSAID |

61.3 |

65.3 |

Efficacy

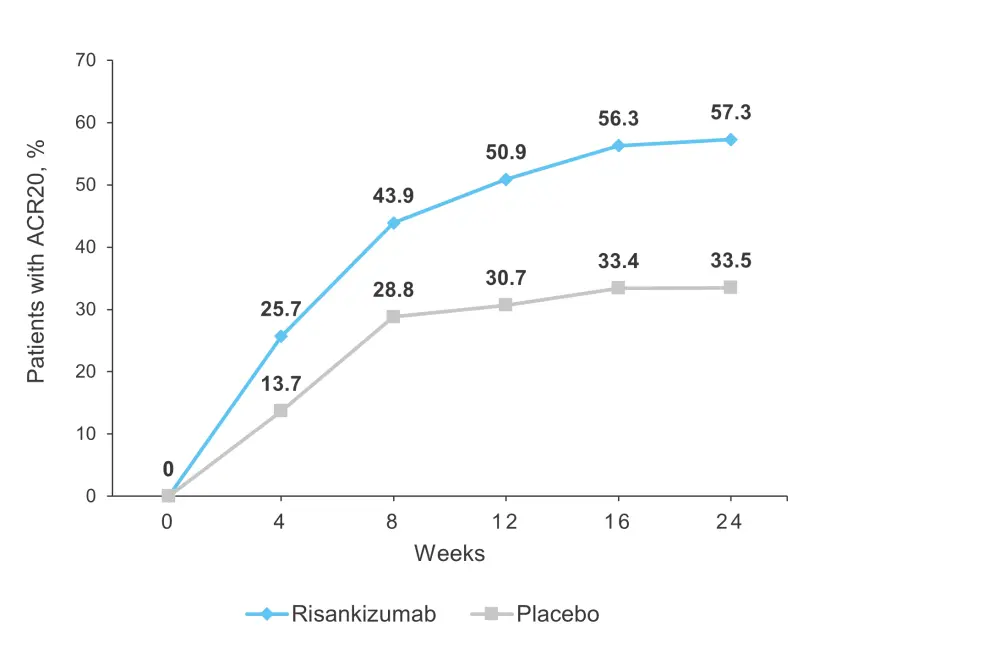

A greater proportion of patients in the risankizumab group achieved a 20% improvement in American College of Rheumatology score (ACR20) at Week 4 compared with those in the placebo group, and the improvement continued through Week 16 (secondary endpoint) and to Week 24 (primary endpoint; 57.3% vs 33.5%; p<0.001; Table 2; Figure 2).

Table 2. Efficacy outcomes*

|

ACR20/50/70, 20/50/70% improvement in American College of Rheumatology score; CI, confidence interval; FACIT-Fatigue, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue Questionnaire; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; LDI, Leeds Dactylitis Index; LEI, Leeds Enthesitis Index; MDA, minimal disease activity; mNAPSI, modified Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; PASI 90, ≥90% reduction in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PGA-F, Physician’s Global Assessment of Fingernail Psoriasis; PsA-mTSS, psoriatic arthritis-modified Total Sharp Score; SF-36 PCS, 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey Physical Component Summary. |

||||

|

Endpoint, % |

Risankizumab 150 mg |

Placebo |

Difference (95% CI) |

p value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Primary endpoint at Week 24 |

||||

|

ACR20 |

57.3 |

33.5 |

24.0 |

<0.001 |

|

Ranked secondary endpoints at Week 24 |

||||

|

Mean change in HAQ-DI |

−0.31 |

−0.11 |

−0.20 |

<0.001 |

|

PASI 90‡ |

52.3 |

9.9 |

42.5 |

<0.001 |

|

ACR20 at Week 16 |

56.3 |

33.4 |

23.1 |

<0.001 |

|

MDA |

25.0 |

10.2 |

14.8 |

<0.001 |

|

Mean change in mNAPSI§ |

−9.8 |

−5.6 |

−4.2 |

<0.001 |

|

Mean change in PGA-F§ |

−0.8 |

−0.4 |

−0.4 |

<0.001 |

|

Resolution of enthesitis‖ |

48.4 |

34.8 |

13.9 |

<0.001 |

|

Resolution of dactylitis¶ |

68.1 |

51.0 |

16.9 |

<0.001 |

|

Mean change in PsA-mTSS |

0.23 |

0.32 |

−0.09 |

0.50 |

|

Mean change in SF-36 PCS |

6.5 |

3.2 |

3.3 |

<0.001 |

|

Mean change in FACIT-Fatigue |

6.5 |

3.9 |

2.6 |

<0.001 |

|

Non-ranked secondary endpoints at Week 24 |

||||

|

ACR50 |

33.4 |

11.3 |

22.2 |

<0.001 |

|

ACR70 |

15.3 |

4.7 |

10.5 |

<0.001 |

Figure 2. ACR20 response over time*

ACR20, 20% improvement in American College of Rheumatology score.

*Adapted from Kristensen, et al.1

The proportion of patients achieving ACR20 at Week 24 was also significantly higher for the risankizumab group in all the prespecified subgroups defined by demographics (age, sex, and body mass index), baseline disease characteristics (duration of PsA, presence of enthesitis, and presence of dactylitis), and use of prior concomitant therapy. In addition, ACR20 at Week 24 was significantly higher in patients treated with risankizumab compared with placebo, irrespective of whether patients received concomitant csDMARDs (57.9% vs 35.9%) or risankizumab monotherapy (55.5% vs 26.2%). Similarly, the risankizumab group showed a greater proportion of patients achieving ACR50 and ACR70 at Week 24 compared to placebo.

The proportion of patients achieving the first eight ranked secondary endpoints, including skin and nail psoriasis endpoints, minimal disease activity, and resolution of enthesitis and dactylitis, was significantly higher for patients treated with risankizumab compared to placebo (p < 0.001; Table 2).

Safety

Both the risankizumab and placebo groups demonstrated similar treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs; 40.4% vs 38.7%) and serious adverse events (SAEs; 2.5% vs 3.7%). Frequently reported TEAEs in ≥2% of patients in either group included nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory infection, increased alanine transaminase, increased aspartate transaminase, and headache. The rate of serious infections was comparable between the two groups and TEAEs leading to study discontinuation were rare (Table 3). There was one death at Week 13 in the risankizumab group due to urosepsis.

Table 3. Safety outcomes*

|

SAE, serious adverse event; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event. |

||

|

Adverse event, % |

Risankizumab 150 mg |

Placebo |

|---|---|---|

|

TEAEs |

40.4 |

38.7 |

|

SAEs† |

2.5 |

3.7 |

|

Severe TEAEs† |

2.1 |

1.9 |

|

TEAE leading to discontinuation of study drug |

0.8 |

0.8 |

|

Death |

0.2‡ |

0 |

|

Serious infections§ |

1.0 |

1.2 |

|

Herpes Zoster‖ |

0.4 |

0.2 |

|

Injection site reactions¶ |

0.6 |

0 |

Conclusion

The KEEPsAKE-1 study demonstrated that risankizumab significantly improved the clinical manifestations of PsA in patients with csDMARD inadequate response. Both primary and secondary endpoints were achieved in a greater proportion in the risankizumab group compared with the placebo group. Risankizumab showed continued efficacy irrespective of concomitant csDMARD therapy. Patients treated with risankizumab demonstrated a comparable safety profile to patients receiving placebo. The findings are limited by the availability of short-term data; however, the ongoing extension of the study will further evaluate long-term safety. In terms of generalizability of the findings, this was restricted by the selection criteria of the study population. Overall, risankizumab demonstrates potential as a treatment option for patients in whom standard therapies are insufficient.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with plaque psoriasis do you see per month?