All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The pso Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the pso Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The pso and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The PsOPsA Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported by educational grants. We would like to express our gratitude to the following companies for their support: UCB, for website development, launch, and ongoing maintenance; UCB, for educational content and news updates. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis content recommended for you

Systemic treatment in elderly patients with psoriasis

Do you know... Elderly patients (greater than or equal to 65 years) place a different emphasis on treatment preferences compared with younger patients. In a study of goals and preferences by van Winden, et al., which one of the following options was not a priority for elderly patients?

Elderly patients with psoriasis are a heterogenous group of patients, which makes their treatment challenging.1 Patients may be impacted by differing levels of frailty, comorbidities, immunosenescence, and comedication. Compounding these issues is the paucity of evidence-based guidance for this population, as they are often excluded from randomized controlled trials due to age, comorbidities, or other prescribed medications they take.1

During the 7th Congress of the Skin Inflammation and Psoriasis International Network (SPIN), Elke ter Haar1 gave a presentation on insights into elderly patients with psoriasis and examined the issues around using systemic treatments in this population.

Disease severity1

In this presentation, ter Haar highlighted that psoriasis disease severity (measured using the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index [PASI]/body surface area) was mostly comparable between younger and older patients. In addition, the impact of psoriasis on quality of life assessed using the Daily Life Quality Index (DL-QI) questionnaire was also similar between younger and older patients. It was noted that there was an increased percentage of adults ≥65 years of age who gave the non-relevant response (60.7%) compared with 31.3% of younger adults (<65 years), which may result in an underestimation of the DL-QI score. These non-relevant responses were mostly regarding questions on work (49.2%) and sports (30.3%). While this can be corrected for using a tool called DLQI-Relevant, this was not used in this study.

Treatment patterns1

Despite experiencing a similar level of severe disease compared with younger patients, older patients tended to receive systemic therapy less frequently. There could be multiple reasons for this difference, including the following:

- Topical or UV therapy may be considered sufficient for the needs of this population

- Older adults may have different treatment goals

- Older patients may be more reluctant to try systemic therapy compared with younger patients

- The safety profile of systemic therapy, including a greater number of contraindications compared with other treatments

Treatment goals and preferences2

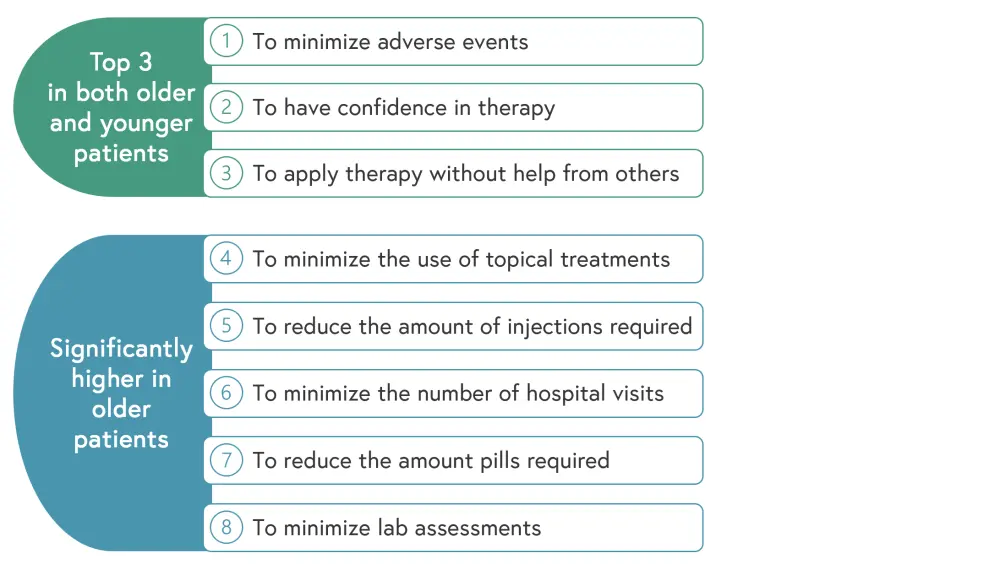

In a study of goals and preferences, van Winden, et al.2 found that both patient groups (above or below 65 years of age) stated that their treatment goals were to be free of scaling and redness and have complete clearance of psoriasis. Figure 1 shows that while the top three patient treatment preferences were the same between the age groups, the older patients ranked numbers 4−8 as significantly more important than patients < 65 years old.

Figure 1. Treatment preferences for older (aged ≥65 years) and younger (aged <65 years) patients with psoriasis*

*Data from van Winden, et al.2

Treatment reluctance3

A mixed method study was conducted via surveys with dermatologists and residents in the Netherlands to examine systemic use in older patients. The results of this study showed that while 68.5% of the healthcare professionals (HCPs) surveyed were not reluctant to use systemic therapy in older patients, 26% do end up prescribing less systemic therapy in these populations. Furthermore, 68.1% perform additional actions, such a modifying the dose and/or increasing monitoring.

Reasons for these differences between treating younger and older patients included a concern that elderly populations may have more comorbidities and comedication. In turn, HCPs were concerned about adverse events (AEs), particularly irreversible AEs.

The HCPs were asked how this could be improved in older patients and the suggestions they gave included the following:

- More evidence-based guidance

- More education regarding skin disease and geriatric medicine, including frailty issues

- Longer consultations to manage these frail patients who may have multiple comorbidities or experience cognitive impairment

Safety profile of systemic treatments1

A systematic review of the safety and effectiveness of systemic treatments was undertaken in patients <65 years and ≥65 years. The results of this study found that the effectiveness of systemic treatment was not influenced by age but there was little in the way of safety data available. Older patients did show an increase in laboratory deviations compared with younger patients.

The study also looked at the use of biologic agents and found that infections were the most common AEs recorded regardless of age.

A multicenter retrospective chart study was also performed in the Netherlands, which solely focused on older patients (≥65 years; n = 230). This study found that 84% of patients had comorbidities and 40% used five or more chronic medications. In this group of patients, systemic therapy was the most common treatment used, although conventional therapies (29%) were favored over biologics (17%).

The AEs in patients treated with systemic therapy (n = 117; 176 treatments; 390 patient-years) were examined and it was found that older patients experienced a greater number of AEs. However, most of these AEs were mild and reversible, and only 12 serious AEs were recorded.

Biologic use in older patients4

Finally, ter Haar, et al.4 compared drug survival of biologics between patients <65 years and ≥65 years old (n = 890; of which n = 102 were ≥65 years). No significant difference was found between the two age groups regarding incidence of treatment discontinuation (all reasons, including AEs, ineffectiveness, and other, which included pregnancy, COVID-19, and patient’s decision; p = 0.144) or for discontinuation due to AEs (p = 0.913) after 5 years. However, patients aged ≥65 years were significantly more likely to discontinue treatment due to perceived ineffectiveness than younger patients (p = 0.006). PASI scores at the moment of treatment discontinuation were investigated but no significant difference was found between the age groups (p = 0.347).

Elke ter Haar suggests that these apparent conflicting data may be the result of the differing treatment goals and the complications associated with treating older patients, such as comorbidities, frailty, and comedication.

Conclusion

Patients ≥65 years old are less likely to use systemic therapy due to a combination of patient preferences and HCP concerns despite efficacy being similar in this group compared with younger patients. Safety data in elderly patients are limited but ter Haar, et al. feel this should not prevent these patients from receiving therapy. While older patients may have more AEs, most are mild and reversible. Treatment with biologics in patients ≥65 years old with psoriasis seems to be an effective option but more evidence-based studies would be of benefit to HCPs, along with increased education on geriatric medicine.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with plaque psoriasis do you see per month?