All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The pso Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the pso Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The pso and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The PsOPsA Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported by educational grants. We would like to express our gratitude to the following companies for their support: UCB, for website development, launch, and ongoing maintenance; UCB, for educational content and news updates. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis content recommended for you

Guest article | Management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in patients with comorbidities: A focus on liver disease

Featured:

Do you know... Which of the following treatments has been linked to an increased incidence of liver disease in patients with psoriasis?

The Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis Hub is pleased to present a guest article from Lija James, Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Psoriatic disease is a recognized multi-system disease, and the symptoms vary from one person to another depending on the severity and clinical manifestations of the disease.1 It is well known that psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is closely related to psoriasis (PsO) and can affect the spine, peripheral joints, and entheses. In European patients with PsO, PsA is present in approximately 23% of patients and in 25% of patients with moderate-to-severe PsO.2

Comorbidities

The disease is commonly associated with several comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), obesity, metabolic syndrome, liver disease, mood disorders, chronic infections, cancers, osteoporosis, and chronic pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia.3 In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 12 studies, the risk of all-cause mortality was evaluated in patients with PsO. The study found that PsO patients were at a greater risk of all-cause mortality, which increased with the severity of the disease. Further, a significantly higher cancer mortality risk was associated with severe skin disease. The mortality risk associated with liver disease, kidney disease, and infection was significantly higher, regardless of severity. In light of this study, clinicians should take into account comorbidity screening and provide necessary patient counseling as part of their management plan.4

Liver disease

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a broad term for the accumulation of fat in the liver. A healthy liver should contain very little fat or none. As NAFLD progresses, it can manifest in several stages, from simple steatosis (fat accumulation), steatohepatitis (liver injury with inflammation), to cirrhosis (irreversible fibrosis from increased collagen deposition), and hepatocellular carcinoma.5

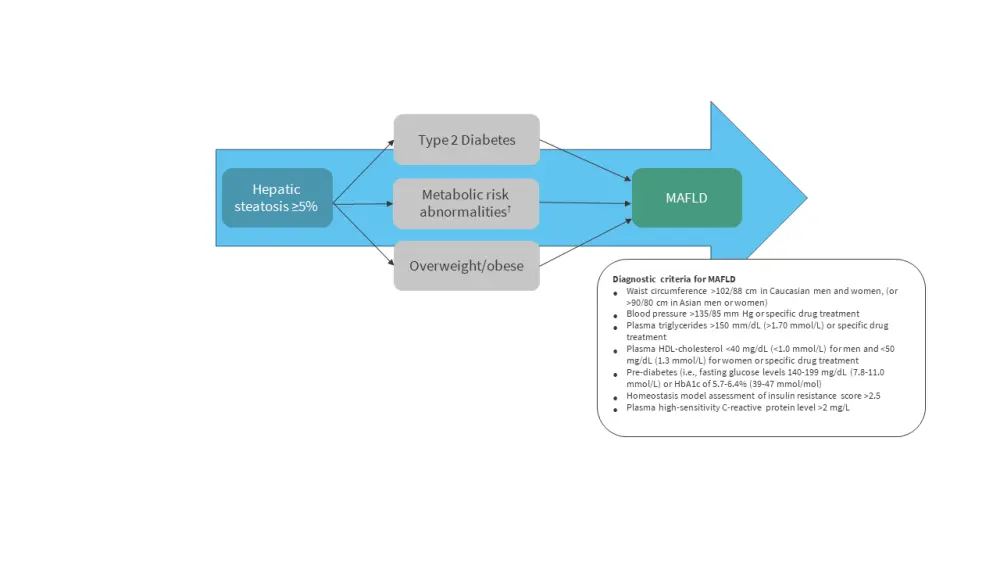

Recently, an international panel using a consensus-driven process proposed a concept for a new multi-systemic condition called ‘Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease’ (MAFLD), which includes metabolic disorders and is independent of alcohol consumption (Figure 1).6 The diagnostic criteria do not require the absence of other liver diseases (unlike NAFLD).5 This reflects the complex metabolic dysregulation pathways involved in this disorder, and it may be helpful in identifying patients at high risk for this condition.7

Figure 1. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease*

HDL, high-density lipoprotein; MAFLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease.

*Adapted from Gofton et al.5

Evidence of liver disease in PsO and PsA

The prevalence of MAFLD is increasing, making it important to study liver disease in patients with psoriatic disease. In the UK, one in three people suffers from the early stages of NAFLD.8 Several studies have linked PsO to NAFLD in adult patients from the U.S.,9 Holland,10 and South-Asian regions.11 A meta-analysis of 249,933 patients with PsO published in 2022 found that the PsO group had a nearly two-fold increased risk of developing NAFLD compared to the control group. Also, patients with NAFLD had more severe skin disease, measured by the psoriasis area and severity index.12

The relationship between liver disease and PsA has, however, been examined in limited studies. The results of a systematic review of three case-control studies concluded that patients with PsA are at increased risk of developing NAFLD (odds ratio [OR]: 2.25, 95% CI 1.37–3.71).13 The most significant study that explored this further was a cohort study (PsO, n = 197,130; PsA, n = 12,308; and rheumatoid arthritis [RA], n = 54,251) in which the outcomes were assessed in terms of any liver disease, NAFLD, and cirrhosis. According to PsO results, the patients had a greater chance of developing advanced liver fibrosis than matched controls. Secondly, the overall prevalence of liver disease was related to the severity of PsO based on the body surface area. There was an increased risk of NAFLD among PsO and PsA patients, even among those who had not been exposed to systematic therapy.14

Pathophysiology

The causal relationship between psoriatic disease and frequently observed comorbidities is not fully understood. Many of the comorbid conditions share similar 'risk factors', including insulin resistance and other metabolic mechanisms such as inflammation and fibrosis.15 A chronic low-grade inflammatory state appears to be the most significant link between MAFLD and psoriasis.16 A U.S. study further concluded that patients with hepatic steatosis were more likely to develop fibrosis if they were insulin-resistant. An imaging study combined with serological markers showed that insulin resistance can lead to fatty acid accumulation, resulting in 'lipotoxicity'. In turn, oxidative damage leads to inflammation and fibrosis, emphasizing the importance of the relationship between metabolic aspects of the disease and liver fibrosis.17

Several molecular studies have been conducted to identify common cytokine pathways involved in inflammation. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a), interleukin 23 (IL-23), and IL-17 are pro-inflammatory cytokines that play a significant role in both the onset and progression of PsA18. In particular, IL-17 may be the pathogenic link between psoriasis and MAFLD. As well as inducing hepatic inflammation via T cell-mediated responses, IL-17 has also been shown to cause insulin resistance in mouse models.19,20 Additionally, clinical studies have shown that inflammation in PsO extends deeper than the skin, with high levels of these cytokines and activated immune cells found in the serum and other organs.21

Treatments

There are a few key considerations when deciding treatment for patients with liver disease. Commonly used conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, such as methotrexate, have shown to cause liver disease.

Gelfand et al. published the first population-based cohort study comparing patients with PsO, PsA, and RA receiving methotrexate after adjusting for comorbidities and methotrexate dose. Patients with PsO receiving methotrexate were significantly more likely to develop mild liver disease (hazard ratio [HR], 2.22), moderate to severe liver disease (HR, 1.56), cirrhosis (HR, 3.38), and hospitalization due to cirrhosis (HR, 2.25) compared with patients with RA receiving methotrexate. Additionally, the PsA group had significantly elevated risk of mild liver disease (HR, 1.27) and cirrhosis (HR, 1.63) compared with the RA group. A key message from this study is to emphasize that patients with PsO receiving methotrexate were more likely to develop liver disease than patients with RA receiving methotrexate. Therefore, strict liver monitoring is recommended for these patients.22

There are multiple mechanisms responsible for hepatotoxicity in biological and synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, which makes drug-induced liver injury (DILI) a challenge. For example, hepatocellular and cholestatic patterns of injury, reactivation of hepatitis B, and autoimmune hepatitis are common for all anti-TNF inhibitors used in psoriatic disease.23 While some treatments adversely affect the liver, others are helpful and are associated with improved liver outcomes. This is thought to be linked to liver inflammation secondary to disease activity.

A recent study showed 82% of patients with PsO (n = 65) had MAFLD. The median psoriasis area and severity index were 11.5 and 6.3 in patients with MAFLD and no MAFLD, respectively. This confirms the risk of liver disease associated with inflammation in PsO and that it is not confined to the skin lesions. Moreover, when treated with an IL-17 inhibitor, the NAFLD fibrosis score improved.24 Therefore, treatment with the right medication not only results in achieving minimal disease activity but also reduces the burden of comorbidities, modifies metabolic risk factors, and improves overall health-related quality of life.

Conclusion

Patients with PsO and PsA have a high prevalence of liver disease, specifically MAFLD. The comorbidities associated with this disease affect more than just physical health. A number of targeted therapeutics are currently available that are effective in treating the disease and associated MAFLD. A multidisciplinary approach and a tailored approach are needed to make the best therapeutic decision for psoriatic disease.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with plaque psoriasis do you see per month?

Laura Coates

Laura Coates Lija James

Lija James