All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The pso Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the pso Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The pso and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The PsOPsA Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported by educational grants. We would like to express our gratitude to the following companies for their support: UCB, for website development, launch, and ongoing maintenance; UCB, for educational content and news updates. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis content recommended for you

Efficacy of probiotics for psoriasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis

The pathogenesis of psoriasis is thought to be linked to the adaptive immune system, and traditional treatments for psoriasis have focused on reducing the skin inflammation caused by immune hyperactivation. The ‘gut-skin axis’ is a theory that the health of the gut is linked to skin homeostasis and improving the gut microbiome can change immune responses. Therefore, it is theorized that using probiotics could improve the symptoms of psoriasis.

Here, we summarize a systematic review and meta-analysis by Wei et al.1 published in the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology on the efficacy of probiotics in patients with psoriasis.

Methods1

- A search was performed in various databases up to November 10, 2023, with the search strategy: “probiotic” and "psoriasis" or “psoriasis pustulosis of palm”.

- Trials were included in the meta-analysis if the patients had a diagnosis of psoriasis and were treated with probiotic, and a control group that was treated with placebo.

- Studies were required to report Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) and /or Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI).

Key findings1

- A total of 5 trials with 286 patients were included in this study. The characteristics of the included trials are shown in Table 1. All studies used PASI and DLQI to measure outcomes, apart from trial 5 which used only PASI.

Table 1. Trial characteristics*

|

Trial |

Interventions |

Probiotic strain |

Duration (months) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Probiotic |

Control |

|||

|

1. Suriano, et al., 2023.2 |

Standard of care plus probiotics |

Standard of care plus placebo |

Lactobacillus rhamnosus |

6 |

|

2. Moludi, et al., 2021.3 |

Probiotic (n = 25) |

Maltodextrin capsule (n = 25) |

Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium lactis, and Bifidobacterium langum |

2 |

|

3. Akbarzadeh, et al., 2022.4 |

Synbiotic product and |

Hydrocortisone and placebo (n = 25) |

Lactobacillus strains, Bifido-bacteria strains, Streptococcus thermophilus, plus fructo-oligosaccharides |

3 |

|

4. Gilli, et al., 2023.5 |

Probiotic (n = 18) |

Placebo (n = 17) |

Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium lactis, and Bifidobacterium langum |

2 |

|

5. Moludi, et al., 2022.6 |

Probiotic (n = 23) |

Placebo (n = 23) |

Lactobacillus rhamnosus |

2 |

|

*Data from Wei, et al.1 |

||||

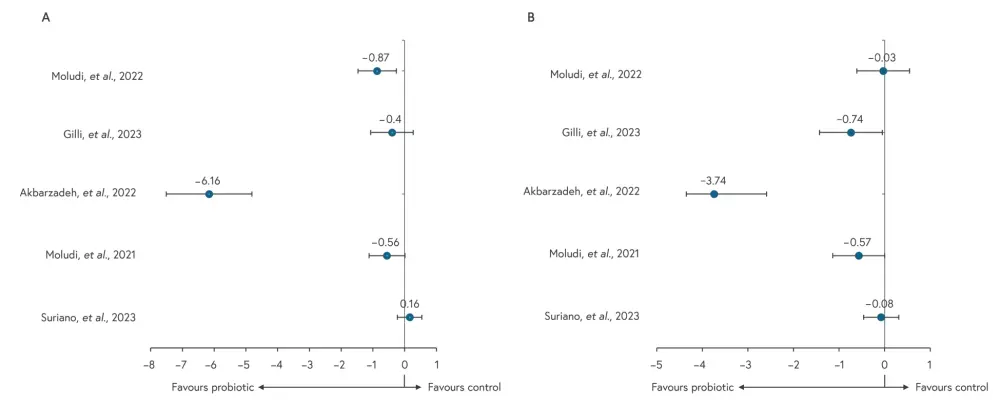

- In general, PASI scores were significantly lower (p < 0.00001) in the probiotic group compared with the placebo group (Figure 1A).

- Overall, DLQI scores were also lower in the probiotic group compared with the placebo group (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. The mean difference in A PASI and B DLQI between the test and control groups in each trial*

DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index.

*Adapted from Wei, et al.1

|

Key learnings |

|---|

|

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with plaque psoriasis do you see per month?