All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The pso Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the pso Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The pso and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The PsOPsA Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported by educational grants. We would like to express our gratitude to the following companies for their support: UCB, for website development, launch, and ongoing maintenance; UCB, for educational content and news updates. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis content recommended for you

Editorial theme | Precision versus personalized medicine in psoriasis and PsA clinical practice

Do you know... According to a prospective study by Menter et al., what proportion of patients discontinued treatment with a biologic within the first year due to a lack of efficacy?

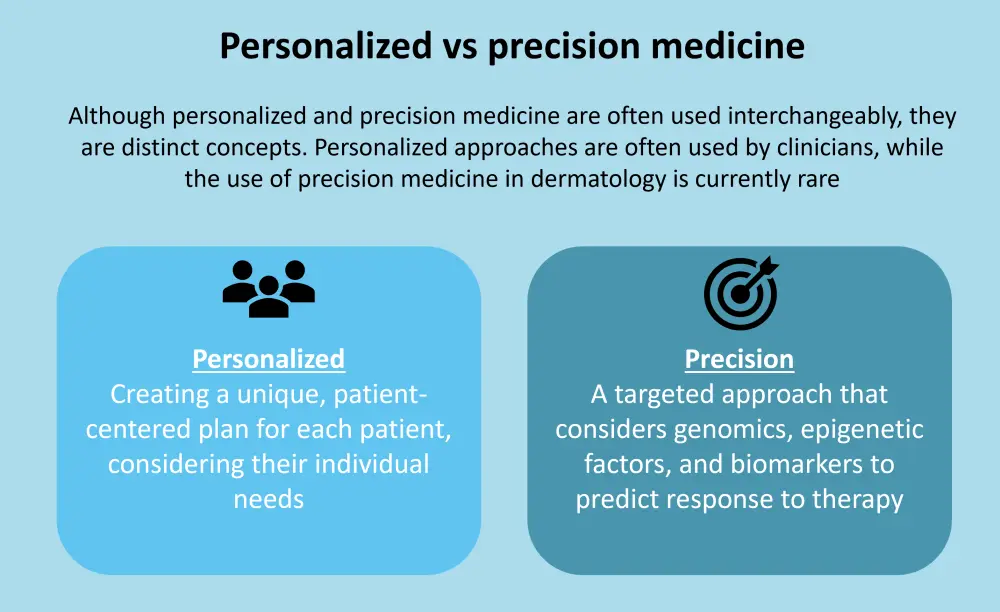

With an increasing number of therapeutic options available for the treatment of psoriasis, precision medicine could aid in the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA).1 Although clinicians often use personalized medicine, it does not take into account the response to therapy.1 The differences between personalized and precision medicine are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Personalized vs precision medicine*

*Data from Zarika, et al.1

Why is precision medicine necessary?

Treating psoriasis without a precision medicine approach can lead to trial-and-error, with multiple follow-up visits necessary to ensure treatment efficacy.1 Response rates seen in clinical trials may not be reflected in the real world, meaning treatment switching is needed for 10–75% of patients within the first year.1 A prospective study showed that within the first year of treatment with a biologic, 23% of patients discontinued due to a lack of efficacy.4 Another study revealed that ~87% of treatment switching occurred within the first two years of treatment.5 Using a precision medicine approach could reduce treatment switching or discontinuation by identifying the optimal treatment, leading to quicker disease clearance.1 Additionally, it could avoid the possible adverse effects of multiple medications and reduce the financial burden on patients and the healthcare system.1

Current perspectives

Treat-to-target in PsA6

Approximately 30–40% of patients with PsA will not reach an adequate treatment response. Currently, there are no biomarkers that can predict treatment response in PsA. The suggested strategy is to use a treat-to-target approach to treat the prevalent domains. Noviani et al.6 summarized existing published trials of efficacies of different classes of therapeutic agents for various PsA domains, which can act as a guide for treatment selection (Table 1). Ideally, treatments should be individualized based on the most affected domains for each patient. However, treatment selection is unlikely to be straightforward in real-world scenarios, and there is a lack of comparative studies of treatments in patients with different affected domains. Therefore, each patient should be considered on an individual basis. In addition, the management of PsA will be greatly enhanced by the availability biomarkers that could predict responses to therapies.

Table 1. How to choose a biologic based on the prevalent domains involved*

footer

Biomarkers and genetics3

There have been many studies into predictive biomarkers, yet none of these have made it to clinical practice yet. Associations between drug responses and genetic polymorphisms differ between populations. Therefore, there may be population-specific genetic biomarkers that could predict drug responses. The TNF-α and TNFRSF1B genes have been widely studied, with results suggesting that some polymorphisms in these genes have been associated with a better response to anti-TNF-α drugs. In particular, the HLA-Cw*06 allele has been investigated for an effect on response to adalimumab, infliximab, and etanercept. A study by Coto-Segura7 showed that HLA-Cw*06 positive patients had an improved response to adalimumab compared to those without the allele. However, in a study by Gallo et al.,8 it was found that HLA-Cw*06 positive patients were less responsive to treatment with adalimumab, infliximab, and etanercept.

The effect of HLA-Cw*06 on the ustekinumab response is more consistent. Multiple studies have suggested that patients who are positive for the allele achieve higher response rates than those who are negative. However, ustekinumab generally has a high response rate regardless of the presence of the allele, which may reduce the usefulness of HLA-Cw*06 as a biomarker.

Future perspectives

Guidelines1

There is a lack of guidance available on which biomarkers can be used to help clinicians decide on an appropriate biologic for each patient. Therefore, for the long-term feasibility of precision medicine, additional guidelines on how genetics and biomarkers can be used to manage psoriasis and PsA are needed.

Conclusion

Precision medicine is an evolving field that will allow for continuous improvement in the effectiveness of patient management. Utilizing biomarkers and genetics can assist in the selection of appropriate biologics for each patient, reducing the need for treatment switching. By moving from a trial-and-error approach to precision medicine, patients will experience quicker clinical improvement with reduced adverse events, ultimately improving patient quality of life.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with plaque psoriasis do you see per month?