All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The pso Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the pso Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The pso and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The PsOPsA Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported by educational grants. We would like to express our gratitude to the following companies for their support: UCB, founding supporter. The funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis content recommended for you

Current guidelines for the treatment and management of PsA from the EULAR and the ACR

Do you know... According to the EULAR recommendations for PsA, what should the first-line pharmacological non-topical treatment for predominant peripheral PsA include?

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic systemic inflammatory condition manifesting as peripheral arthritis, spondylitis, dactylitis, enthesitis, and psoriasis of the skin and nails. In addition, PsA may also manifest as inflammatory bowel disease and uveitis, and it may be associated with cardiovascular, psychological, and metabolic comorbidities, which impact patient functioning and quality of life. Therapeutic options have increased over the past 10 years, with both conventional and targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and targeted biological agents now available for PsA treatment.1

Vivekanantham et al.1 recently published a summary of the current pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment recommendations set out by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR); below we highlight some key points of this review.

Nonpharmacological management

Treatment plans for PsA should not be limited to pharmacological interventions, but should offer comprehensive support, including components such as

- patient education;

- dietary and lifestyle advice, including weight loss and smoking cessation;

- rest and exercise;

- and physical and occupational therapy.

For most patients, pain is the most predominant symptom and manifests as a multifaceted and complex experience resulting from tissue damage and inflammation, as well as individual factors, including mood, obesity, illness beliefs, and age. The EULAR guidelines recommend that clinicians follow a patient-centered framework aligned with a biopsychosocial model and to differentiate between localized and generalized nonspecific pain. Pain localized to individual joints or body regions is often associated with peripheral nociceptive input, such as inflammation or tissue damage, and is typically more responsive to pharmacological agents. Generalized pain requires comprehensive management strategies, including rest and exercise, weight loss, and psychosocial support. Due to a lack of pain management approaches specific to PsA, treatment options utilized in rheumatoid arthritis are recommended.

Physical activity and targeted exercises are key elements of nonpharmacological treatment plans, with the EULAR recommending physical activity as part of standard care in patients with inflammatory arthritis, and the ACR recommending low-impact exercise in PsA. Physical exercise is known to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and osteoporosis in the general population, all of which are independently associated with increased morbidity and mortality in patients with PsA. The underlying mechanisms of the benefits of physical activity are likely to include the positive impact of circulating inflammatory levels, such as C-reactive protein, and reduced joint loads from weight loss. Reduced mechanical strain on a patient’s joints can also be achieved through dietary interventions, which not only reduces central adiposity, but can also reduce cardiovascular risk. Smoking cessation is also advised due to its association with cardiovascular events. The ACR recommends weight loss in patients who are overweight or obese and makes a strong recommendation for smoking cessation advice in patients with PsA.

Pharmacological management

Traditional and conventional synthetic DMARDs are recommended by the EULAR as the first-line pharmacological treatment for PsA. In addition, biological therapies that modulate specific cytokine pathways, as well as targeted oral agents, including phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, are also used for PsA treatment. Ustekinumab, which targets interleukin (IL)-12/IL-23 signalling pathways, and secukinumab and ixekizumab, which are IL-7A signalling inhibitors, have shown effectiveness versus placebo in clinical trials, as well as proven superiority over tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors. Targeted synthetic DMARDs have also become available as treatment options for PsA, including apremilast, a PDE4 inhibitor, and tofacitinib, an oral JAK inhibitor licensed for peripheral arthritis. A summary of other available pharmacological treatments is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of the available pharmacological treatments for psoriatic arthritis*

|

CTLA-4 Ig, cytotoxic T lymphocyte associated antigen-4 immunoglobulin; IL, interleukin; JAK, Janus kinase; PDE4, phosphodiesterase 4; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; TNF, tumor necrosis factor. *Adapted from Vivekanantham, et al.1 †Called ‘oral small molecules’ (OSMs) in the American College of Rheumatology guidelines with the addition of apremilast. ‡Methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and leflunomide are grouped as conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in the European League Against Rheumatism recommendations. |

|

|

Treatment type |

Example |

|---|---|

|

Symptomatic therapies |

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, glucocorticoids, local glucocorticoid injections |

|

Oral treatments†,‡ |

Methotrexate, sulfasalazine, cyclosporine, leflunomide |

|

TNF inhibitors |

Etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab, certolizumab pegol |

|

IL-12/23 inhibitor |

Ustekinumab |

|

IL-17A inhibitors |

Secukinumab, ixekizumab |

|

CTLA-4 Ig |

Abatacept |

|

JAK/STAT inhibitor |

Tofacitinib |

|

PDE4 inhibitor |

Apremilast |

Similarities and differences between guidelines

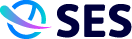

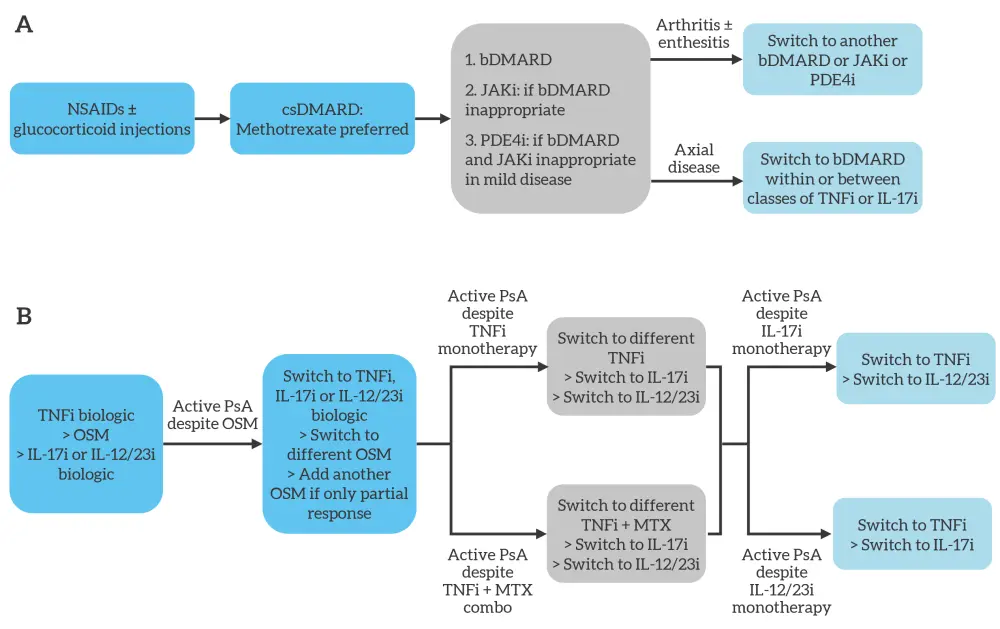

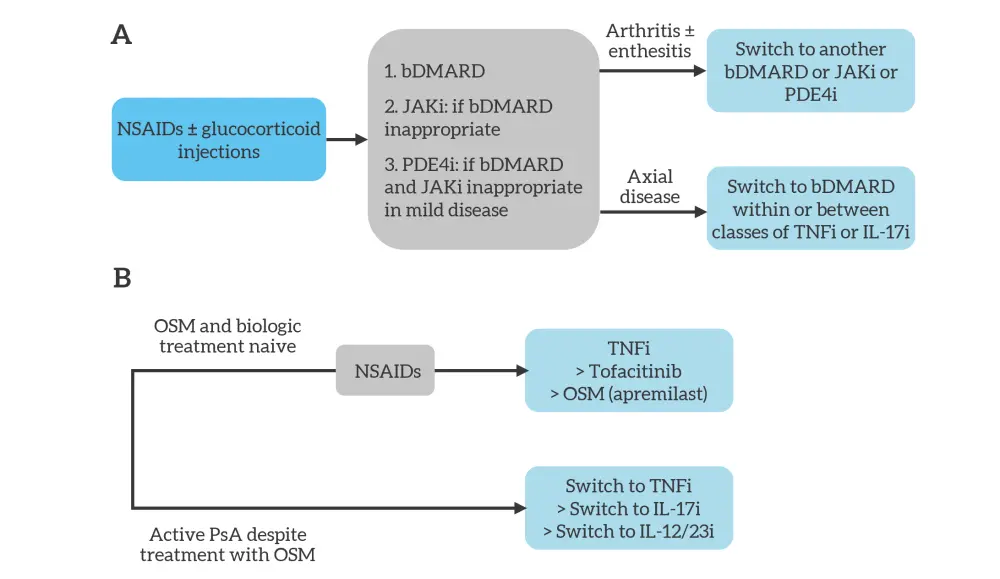

There are similarities in the use of available treatments in the EULAR recommendations and the ACR guidelines, but the treatment algorithms differ. This is due to differences in target healthcare settings, differing methods used to create the guidelines, and the emphasis placed on expert opinion and use of low-quality evidence. The EULAR recommendations have a single algorithm for pharmacological non-topical treatments with a proposed sequencing of administration. The ACR recommendations have several individual figures and tables for each specific situation, with reference to specific medications in preference to another, but the exact order is not specified. The EULAR and ACR treatment algorithms for peripheral PsA, entheseal PsA, and axial PsA are summarized in Figures 1–3. The EULAR recommendations and ACR guidelines also differ when defining disease severity, outlined in Table 2. The EULAR define it based on the presence of poor prognostic factors, whereas the ACR provide specific definitions for severe disease.

Figure 1. Simplified A EULAR and B ACR treatment algorithms for predominant peripheral PsA*

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; bDMARD, biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; EULAR, European League Against Rheumatism; IL-12/23i, interleukin-12/23 inhibitor; IL-17i, interleukin-17 inhibitor; JAKi, Janus kinase inhibitor; MTX, methotrexate; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; OSM, oral small molecule; PDE4i, phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; TNFi, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

*Adapted from Vivekanantham, et al.1

Figure 2. Simplified A EULAR and B ACR treatment algorithms for predominant entheseal PsA*

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; bDMARD, biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; EULAR, European League Against Rheumatism; IL-12/23i, interleukin-12/23 inhibitor; IL-17i, interleukin-17 inhibitor; JAKi, Janus kinase inhibitor; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; OSM, oral small molecule; PDE4i, phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; TNFi, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

*Adapted from Vivekanantham, et al.1

Figure 3. Simplified A EULAR and B ACR treatment algorithms for predominant axial psoriatic arthritis*

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; bDMARD, biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; EULAR, European League Against Rheumatism; IL17i, interleukin-17 inhibitor; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; TNFi, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

*Adapted from Vivekanantham, et al.1

Table 2. Definitions of disease severity*

|

CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; PsA, psoriatic arthritic. |

|

|

EULAR poor prognostic factors |

ACR severe PsA |

|---|---|

|

Structural damage |

Erosive disease |

|

High ESR/CRP |

Elevated markers of inflammation (ESR and CRP) attributable to PsA |

|

Presence of dactylitis |

Long-term damage that interferes with function (i.e., joint deformities) |

|

Presence of nail changes |

Highly active disease that causes a major impairment to quality of life |

|

Active PsA at many sites including dactylitis and enthesitis |

|

|

Function-limiting PsA at a few sites |

|

|

Rapidly progressive disease |

|

Whilst both organizations recommend a treat-to-target approach, this being of particular focus for the EULAR recommendations, the ACR recommendations also lists circumstances where one may consider not using this approach, including if there are concerns related to

- adverse events;

- the cost of treatment;

- and the burden that changes to medication with tighter control may have.

The ACR guidance goes further by outlining recommendations for nonpharmacological management, and the management of patients with active PsA with associated active inflammatory bowel disease, other related comorbidities, and those requiring vaccination. The EULAR has separate guidelines for vaccinations in patients with PsA.

Conclusion

Both pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches must be considered in the management of patients with PsA. Treatment should be tailored according to active PsA domains and comorbidities. The recommendations and guidelines from the EULAR and ACR can be used to support clinicians and ensure patients are optimally managed.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with plaque psoriasis do you see per month?