All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The pso Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the pso Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The pso and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The PsOPsA Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported by educational grants. We would like to express our gratitude to the following companies for their support: UCB, for website development, launch, and ongoing maintenance; UCB, for educational content and news updates. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis content recommended for you

Association between adverse pregnancy outcomes and psoriasis: Findings from a Danish case-control study

Do you know... A recent Danish case-control study by Johnson et al. investigated the association between psoriasis and adverse pregnancy outcomes (APOs). Which APO did the study identify as being most strongly associated with psoriasis?

Psoriasis affects between 2% and 4% of the world’s population, and nearly half of all cases occur in women, mostly of childbearing age.1 Chronic systemic inflammation associated with psoriasis may increase the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes (APOs) by affecting the fertility of women and leading to spontaneous abortion, ectopic pregnancy (EP), intrauterine fetal death, and stillbirth.

Psoriasis shares pathophysiological pathways with other inflammatory diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease, inflammatory arthritis, and psoriatic arthritis (PsA), which have been associated with APOs. In addition, women with psoriasis have a higher prevalence of other risk factors associated with APOs, including obesity, smoking, gestational hypertension, use of nonsteroidal anti‑inflammatory drugs, low socioeconomic status, diabetes, preconception hypertension, thyroid diseases, and low fertility rates.

Here, we summarize the key findings from a nationwide Danish case-control study investigating the association between psoriasis and APOs, which was published by Johansen, et al.1 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology International.

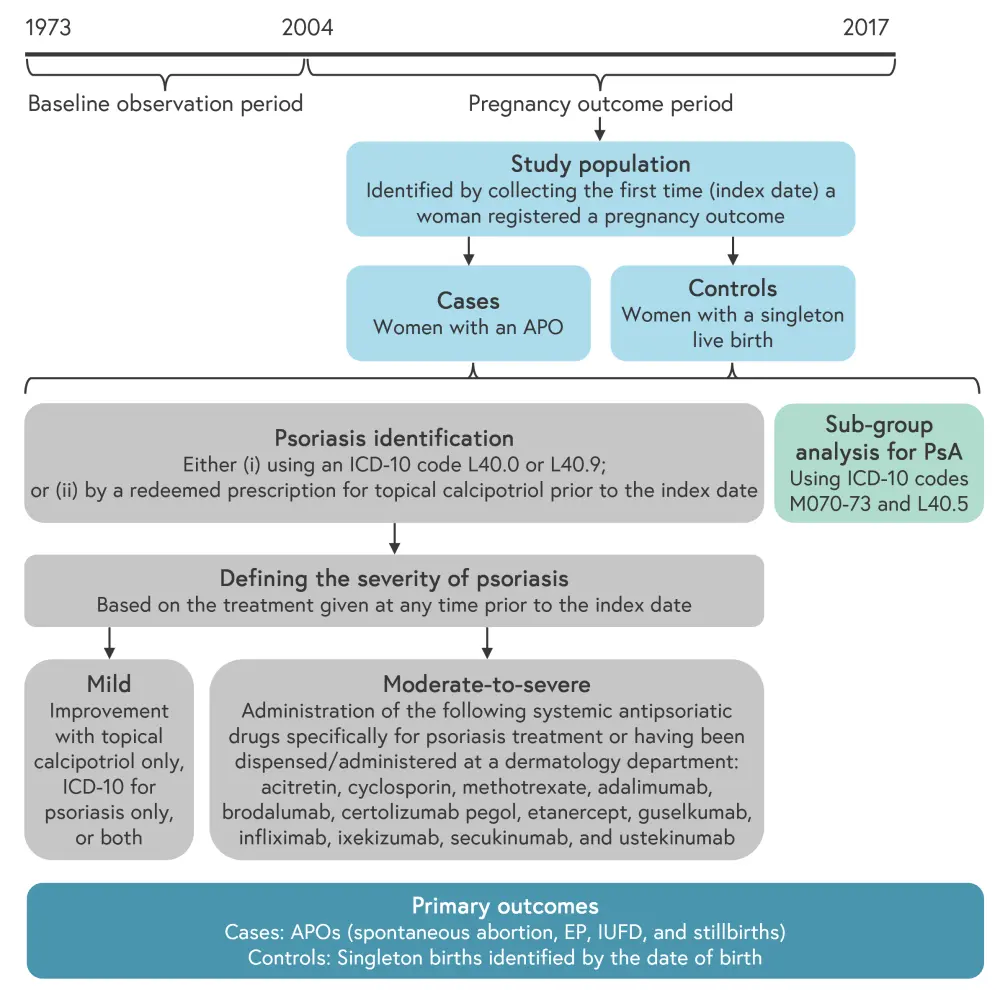

Study design

The design of the Danish case-control study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Study design*

APO, adverse pregnancy outcome; EP, ectopic pregnancy; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision; IUFD, intrauterine fetal death; PsA, psoriatic arthritis.

*Adapted from Johansen, et al.1

Results

A total of 491,274 women were included in the study, of which 6,426 had psoriasis, and the mean age at index date was 30.3 years. There was a higher prevalence of all comorbidities, including pregnancy-related comorbidities, in women with psoriasis (Table 1).

In women with moderate-to-severe psoriasis, there were fewer “1–2 previous live births” reported compared with in those without psoriasis (11.94% vs 22.45%, respectively). The prevalence of 1–2 previous assisted reproductive technology-based treatments was highest in women with moderate-to-severe psoriasis compared with in those with mild psoriasis or those without psoriasis (8.46% vs 5.88% vs 4.40%, respectively).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics (N = 491,274)*

|

BMI, body mass index; NA, not applicable; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SD, standard deviation. |

|

||||

|

Characteristic, % (unless stated otherwise) |

Without psoriasis |

With psoriasis |

Mild psoriasis |

Moderate-to-severe psoriasis |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mean age at index (SD), years |

30.10 (5.14) |

30.40 (5.11) |

30.67 (5.10) |

30.02 (5.25) |

|

|

Mean age at the first registered psoriasis diagnosis (SD), years |

NA |

23.64 (6.58) |

23.74 (6.57) |

20.64 (6.15) |

|

|

Mean duration of psoriasis at index (SD), years |

NA |

7.01 (4.80) |

6.93 (4.77) |

9.38 (4.91) |

|

|

Pregnancy-related comorbidities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gestational diabetes |

2.59 |

3.63 |

3.63 |

3.48 |

|

|

Pre-eclampsia |

4.23 |

5.06 |

5.09 |

3.98 |

|

|

Gestational hypertension |

2.21 |

2.65 |

2.65 |

2.49 |

|

|

Smoking status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Non-smoker |

79.46 |

75.82 |

75.87 |

74.13 |

|

|

Stopped in first trimester |

2.63 |

3.47 |

3.44 |

4.48 |

|

|

Stopped after first trimester |

0.53 |

0.72 |

0.74 |

0.00 |

|

|

Active throughout pregnancy |

10.23 |

13.17 |

13.14 |

13.93 |

|

|

Smoking status unknown |

7.14 |

6.83 |

6.81 |

7.46 |

|

|

Mean BMI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

<18.5 kg/m2 (underweight) |

5.10 |

3.95 |

4.02 |

1.99 |

|

|

18.5–24.9 kg/m2 |

60.75 |

57.63 |

57.85 |

50.75 |

|

|

25.0–29.9 kg/m2 (overweight) |

18.29 |

19.97 |

19.94 |

20.90 |

|

|

≥30.0 kg/m2 (obese) |

4.93 |

4.95 |

4.88 |

6.97 |

|

|

Administered systemic psoriasis treatment during pregnancy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Biologics† |

0.01 |

0.05 |

— |

— |

|

|

Cyclosporin† |

0.00 |

— |

— |

0.00 |

|

|

Redeemed co-medication during pregnancy, n |

|

|

|

|

|

|

NSAIDs |

2,151 |

31 |

31 |

0 |

|

|

Methotrexate† |

6 |

<3 |

0 |

<3 |

|

|

Acitretin |

4 |

3 |

<3 |

<3 |

|

|

Antidepressants† |

1,314 |

22 |

Not shown‡ |

<3 |

|

|

Mean age at the first live birth (SD), years |

28.90 (4.85) |

29.36 (4.95) |

29.37 (4.94) |

29.01 (5.21) |

|

The risk of EP was higher in all women with psoriasis when compared with women without psoriasis (1.50% vs 1.87%, respectively), and this risk remained after adjusting for age, body mass index, and smoking, as shown in Table 2. The post hoc analysis showed that the risk of EP was not affected when adjusting for pelvic inflammatory disease and endometriosis.

The risk of EP was higher in women with mild psoriasis when compared with women without psoriasis (odds ratio [OR], 1.21). EP risk was even higher in women with moderate-to-severe psoriasis (3.98%) when compared with women without psoriasis (1.50%; OR, 2.77), which equated to a 2.48% higher absolute risk of EP.

Table 2. Crude and adjusted models for APOs*

|

CI, confidence interval; EP, ectopic pregnancy; IUFD, intrauterine fetal death; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio. |

||||

|

Characteristic |

Crude† |

Model 1‡ |

Model 2§ |

Model 3‖ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Women without psoriasis vs women with psoriasis |

||||

|

Spontaneous abortion |

1.05 (0.95–1.15) |

1.03 (0.93–1.13) |

1.02 (0.90–1.16) |

1.04 (0.92–1.17) |

|

EP |

1.25 (1.06–1.50) |

1.24 (1.03-1.49) |

1.35 (1.07–1.70) |

1.34 (1.06–1.68) |

|

IUFD |

0.75 (0.42–1.32) |

0.74 (0.42–1.31) |

0.74 (0.40–1.38) |

0.74 (0.40–1.39) |

|

Stillbirth |

1.14 (0.61–2.13) |

1.14 (0.61–2.12) |

0.77 (0.34–1.72) |

0.76 (0.34–1.70) |

|

Live birth |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Women without psoriasis vs women with mild psoriasis |

||||

|

Spontaneous abortion |

1.04 (0.94–1.15) |

1.02 (0.93–1.13) |

1.03 (0.92–1.17) |

1.05 (0.93–1.18) |

|

EP |

1.21 (1.00–1.46) |

1.19 (0.99–1.44) |

1.30 (1.03–1.65) |

1.29 (1.02–1.64) |

|

IUFD |

0.71 (0.39–1.28) |

0.70 (0.39–1.27) |

0.69 (0.36–1.32) |

0.69 (0.36–1.33) |

|

Stillbirth |

1.16 (0.63–2.20) |

1.17 (0.63–2.19) |

0.79 (0.36–1.78) |

0.78 (0.35–1.76) |

|

Live birth |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Women without psoriasis vs women with moderate-to-severe psoriasis |

||||

|

Spontaneous abortion |

1.25 (0.75–2.08) |

1.25 (0.75–2.09) |

0.78 (0.37–1.66) |

0.79 (0.37–1.68) |

|

EP |

2.77 (1.37–5.64) |

2.77 (1.36–5.63) |

2.79 (1.15–6.79) |

2.70 (1.11–6.60) |

|

IUFD |

2.07 (0.29–14.80) |

2.07 (0.30–14.79) |

2.29 (0.32–16.38) |

2.29 (0.32–16.39) |

|

Stillbirth |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Live birth |

— |

— |

— |

— |

PsA subanalysis

A total of 291 (0.06%) women had PsA, of which 171 (58.76%) had an overlapping psoriasis diagnosis. Amongst these women, 127 had mild and 44 had moderate-to-severe psoriasis. The risk of EP was 2-fold in women with PsA compared with women without (regardless of psoriasis diagnosis; crude OR, 2.12) and increased further when adjusting for other risk factors (model 2: OR 2.48; model 3: OR, 2.41).

Conclusion

This study showed that psoriasis was associated with an increased risk of EP. Women with moderate-to-severe psoriasis and PsA had the highest risk of EP. Psoriasis was not associated with an increased risk of spontaneous abortion, intrauterine fetal death, or stillbirth. Johansen, et al. speculate that this association may be due to women with severe psoriatic disease being more susceptible to tubal implantation due to a predominance of T helper type 17 cells (drivers of systemic inflammation), a reduced activity of regulatory T cells, and a microenvironment in the fallopian tubes that is permissive of embryo implantation. The shared immunopathologic pathway with inflammatory bowel disease, which is also associated with an increased risk of EP, strengthens the hypothesis that psoriasis is associated with an increased risk of EP.

Although the study included data from nationwide registries of high quality, validity, and completeness, it was limited by recall, interview, and questionnaire biases. Additionally, information on clinical measurements, including body surface area, psoriasis area severity index, and lifestyle factors (such as alcohol and exercise), were not available. Therefore, further clinical studies exploring the association between antipsoriatic treatment and the inflammatory state and severity of the disease are warranted. In addition, studies of the causality between psoriasis and EP, the pathophysiologic mechanism of psoriasis inflammation, and APOs are needed to confirm the finding of this study. With EP being a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality in the first trimester of pregnancy, the authors call for particular care for women of reproductive age with psoriasis.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with plaque psoriasis do you see per month?