All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The pso Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the pso Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The pso and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The PsOPsA Hub is an independent medical education platform, supported by educational grants. We would like to express our gratitude to the following companies for their support: UCB, for website development, launch, and ongoing maintenance; UCB, for educational content and news updates. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis content recommended for you

An overview of the epidemiology, diagnosis, classification, and management of psoriasis

Do you know... What is the median age in years of psoriasis onset?

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease with well-characterized pathology and it is associated with many other medical conditions. Psoriasis greatly impacts quality of life and many patients with psoriasis feel a considerable effect on their psychosocial well-being. Although psoriasis currently cannot be cured, understanding the management of psoriasis enables early treatment, prevention of associated multimorbidities, lifestyle modifications, and a personalized approach to treatment. Here, we summarize the epidemiology, diagnosis, classification, and management of patients with psoriasis, based on an article published in The Lancet by Griffiths et al.1

Epidemiology

Psoriasis occurs worldwide, affecting over 60 million adults and children, occurring equally in both men and women, presenting at any age with a median age of onset of 33 years, and contributing to a considerable disease burden. Psoriasis occurs more commonly in white adults, with an overall prevalence of 1.5% in Western Europe compared with 0.1% in east Asia. Psoriasis can present earlier in women, with a bimodal onset at the age of 16–22 years and 55–60 years, and may increase the risk of depression and suicidal ideation and behavior compared with the general population.

Classification

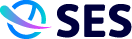

Psoriasis presents with different clinical phenotypes and is classified based on its distinctive morphology (Figure 1A) or location (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Classification based on distinctive A morphology and B location*

*Adapted from Griffiths, et al.1

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of psoriasis is established based on clinical symptoms, history, morphology, and distribution of skin lesions. Patients’ history may be suggestive of family history, potential triggers, the onset of psoriasis, and any indication of psoriatic arthritis. A detailed skin examination should be performed, including of the nails, scalp, flexures, and intergluteal cleft, as well as of genital areas as patients may be embarrassed to discuss genital involvement.

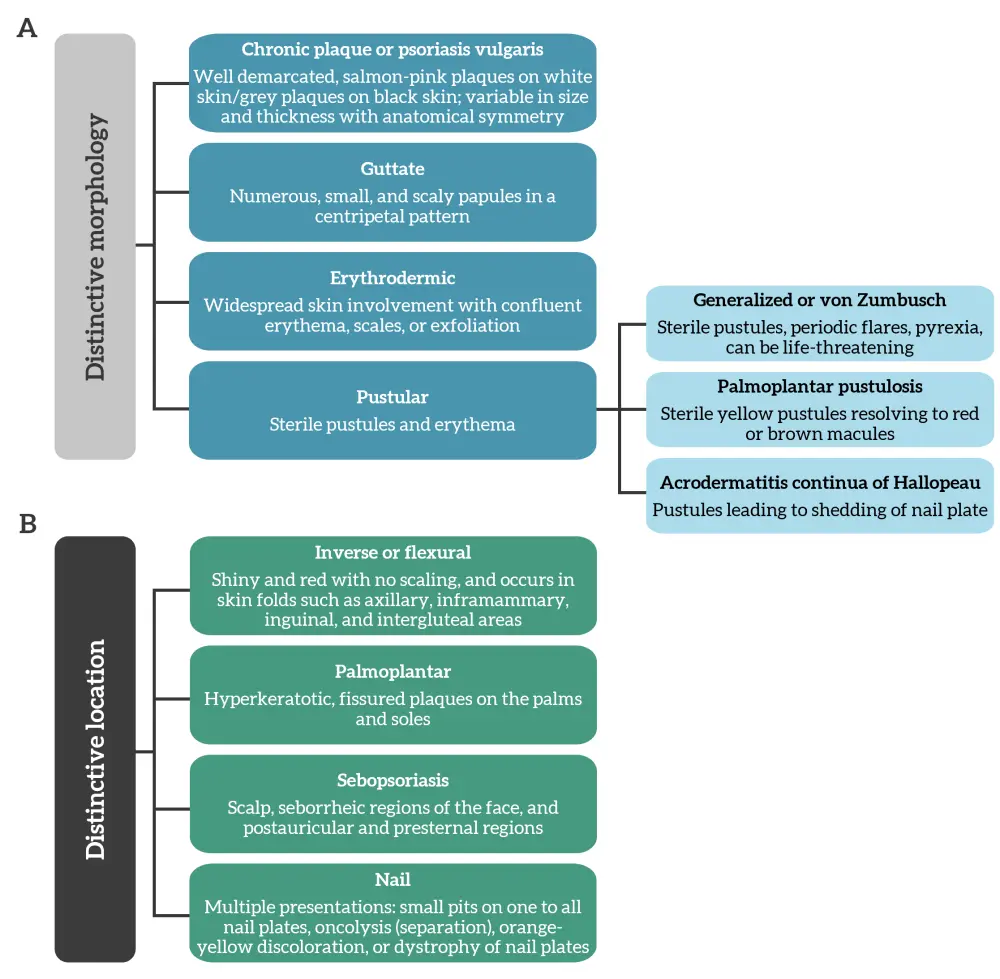

Differential diagnosis of psoriasis is challenging and may include inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic processes that mimic its papulosquamous presentation. Examples of skin conditions that can be mistaken for psoriasis are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Skin diseases that can be mistaken for psoriasis*

*Data from Griffiths, et al.1

Pathophysiology

The histological features of psoriasis include acanthosis (thickening of epidermis), a thinning or absent granular layer, elongated and dilated capillaries, suprapapillary thinning, an inflammatory infiltrate of T cells in the dermis and epidermis, and occasionally clusters of neutrophils in the parakeratotic scale. Immunological and genetic studies have highlighted a role for immune pathways involving interleukin (IL)-17 and IL-23. Other crucial pathways include those involving type 1 interferons and antiviral signaling, NF-κB, and antigen processing and presentation. Heritability is the main risk determinant for psoriasis, with genome-wide association studies identifying many risk loci. HLA-C*06:02 is major genetic risk factor for early-onset psoriasis; however, late-onset disease, psoriatic arthritis, and pustular forms of psoriasis are not associated with HLA-C*06:02. Inheritance of one HLA-C*06:02 allele increases the risk of psoriasis by four- or five-fold, and interaction with a risk variant in the ERAP1 gene further increases the risk of psoriasis.

Psoriasis presentation is dependent on gene-environment interactions and tends to manifest in the presence of environmental triggers, such as stress, infection, alcohol consumption, obesity, drug exposure, and in some cases, sunlight.

Angiogenesis, neutrophil infiltration, and an increased number of T helper (Th)1 cells and Th17 cells are driven by the activation of keratinocytes, which promotes epidermal hyperproliferation and the production of antimicrobial proteins, growth factors, and chemokines. A subset of T cells, tissue-resident memory T cells, persist long-term in epithelial tissue and contribute to immune-mediated diseases, such as psoriasis, when abnormally activated. The persistent nature of tissue-resident memory T cells may explain some features of psoriasis, including recurrence at previous sites of involvement.

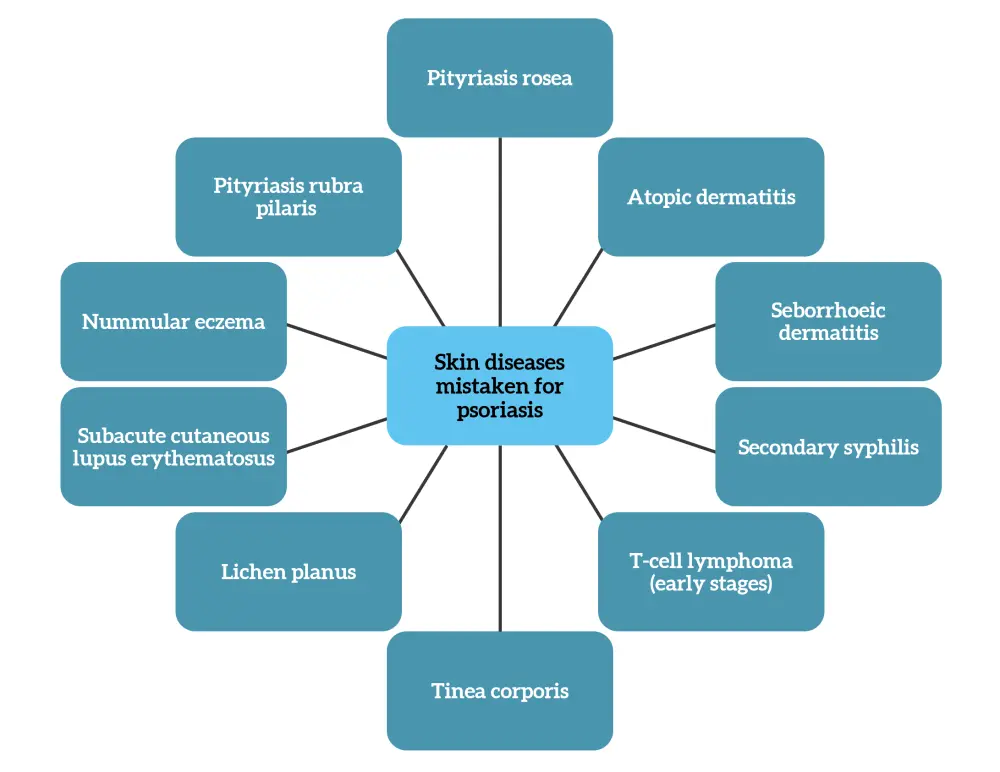

IL-17 and Th17 responses are important drivers of psoriasis and the balance between key cytokine circuits in psoriasis are responsible for the clinical manifestations of different types of psoriasis (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Inflammatory circuits in psoriasis*

A In psoriasis, three interconnected inflammatory circuits are present: (i) Th17 and Tc17 responses driven by an IL-17, IL-23, and a CCL20 feedback circuit (red dotted line); (ii) a type I and type II IFN circuit driven by pDCs and IFN-γ-secreting T cells via a CXCL9 and CXCL10 feedback circuit (green dotted line); and (iii) an IL-36 and neutrophil axis driven by the neutrophil chemokines CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL8 (blue dotted line). B These three circuits are linked to IL-36 and IFN-γ responses via a positive feedback mechanism, supporting Th17 responses, which then activate IL-36 responses in a feed-forward amplification. C The balance between these inflammatory circuits may explain, in part, the clinical heterogeneity of psoriasis: IL-17 responses dominate in plaque psoriasis; IFN responses dominate in paradoxical psoriasis; and IL-36 responses dominate in pustular psoriasis.

*Adapted from Griffiths, et al.1

CLC20, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 20; CXCL, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; ILC3, innate lymphoid cell 3; MΦ, macrophage; pDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cell; Th, T helper; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Disease association

One of the diseases most associated with psoriasis is psoriatic arthritis, a seronegative inflammatory arthritis that occurs in 10–40% of patients with psoriasis. Psoriatic arthritis is generally asymmetrical and affects distal interphalangeal joints, sometimes with axial involvement. Other manifestations include enthesitis and dactylitis. Although psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis have common pathogenetic and immunological features and overlap in some therapies, they are distinct entities in terms of genetics, immunology, and therapeutic response.

Other conditions, such as hypertension, obesity, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease, have been found to have an association with psoriasis. However, these conditions are more commonly regarded as comorbidities and there is a need to establish the true relationship between these conditions and psoriasis to aid the management of these comorbidities along with the management of psoriasis. It is likely that lifestyle-directed therapies could improve clinical outcomes in this population.

Management

Overall treatment goals and strategy

Treatment strategies for psoriasis are based on psoriasis severity, presence of psoriatic arthritis, associated medical conditions, and patient preference and satisfaction. Education sessions and a holistic approach, including advice on smoking cessation, reduction in alcohol intake, weight loss, and improving sleep and exercise, are considered important in the management of psoriasis.

The definition of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis varies worldwide, with the International Psoriasis Council now rejecting the mild, moderate, and severe categories of severity, but instead recommending a dichotomous classification. Patients should be classified as suitable for topical therapy or suitable for systemic therapy. Patients suitable for systemic therapy should fulfill at least one of three criteria: >10% of body surface affected, psoriasis at special sites (scalp, face, palms and soles, or genitalia), and non-response to topical therapy.

Some countries have adopted the concurrent use of biologics, oral agents, and phototherapies for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis.

An increasing worldwide push to adopt a treat-to-target approach, which would include an absolute psoriasis area severity index ≤2, or a physician’s global assessment of clear or almost clear, are achievable and may lead to better control of psoriasis and improved patient outcomes.

Types of therapies

Topical therapy

Topical treatments are a mainstay of psoriasis therapy when the disease is limited to 3–5% of the body surface. All patients experience benefit from the application of emollients, but there is poor adherence to topical treatment. Topical agents include corticosteroids, vitamin D, analogues, calcineurin inhibitors, keratolytics, and combination topical agents, as well as crude coal tar and dithranol, which may be used in day treatment centers and in dermatology apartments.

Phototherapy

Phototherapy is locally immunosuppressive, inhibiting hyperproliferation and angiogenesis, which leads to selective reduction in cutaneous T cells. Modalities of phototherapy include the following:

- Narrowband (311–313 nm) ultraviolet B radiation

- Most commonly used and effective for plaque psoriasis

- Typically administered 2–3 times per week

- Side effects include burning and a slight risk of photocarcinogenesis

- Time-consuming

- Broadband (280–320 nm) ultraviolet B radiation

- Targeted phototherapy

- Oral psoralen ultraviolet A (photochemotherapy)

- Less frequently used due to cumulative risk of skin cancer

Oral systemic therapies

Oral systemic therapies were the mainstay of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis treatment until the advent of biologics. They include methotrexate, ciclosporin, acitretin, fumarates, and apremilast. The mechanism of action, efficacy, and safety profiles of these oral systemic therapies differ considerably (Table 1).

Table 1. Oral systemic therapies for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis*

|

BID, twice a day; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; TNF, tumor necrosis factor. |

||||

|

Oral agent |

Maintenance dose in adults |

Efficacy by Week 16 |

Mechanism of action |

Adverse effects and considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Methotrexate |

15–20 mg/week + folic acid |

36% |

Through 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide transformylase + increased adenosine production |

Hepatoxicity with long-term use |

|

Apremilast |

30 mg BID |

33% |

Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor |

Worsening of depression |

|

Ciclosporin |

≤5 mg/kg/day |

65% or almost clear‡ |

Systemic calcineurin inhibitor |

Hypertension |

|

Fumarates |

Maximum 720 mg/day after gradual titration |

37% |

Inhibit maturation of dendritic cells, induce T cell apoptosis, and interfere with leucocyte extravasation |

High rate of gastrointestinal intolerance |

|

Acitretin |

25–50 mg/day |

47% |

Normalizes keratinocyte proliferation and exerts immunomodulatory effects to decrease proinflammatory cytokines (IL‑6 and IFN‑γ) |

Xerosis |

Biologics

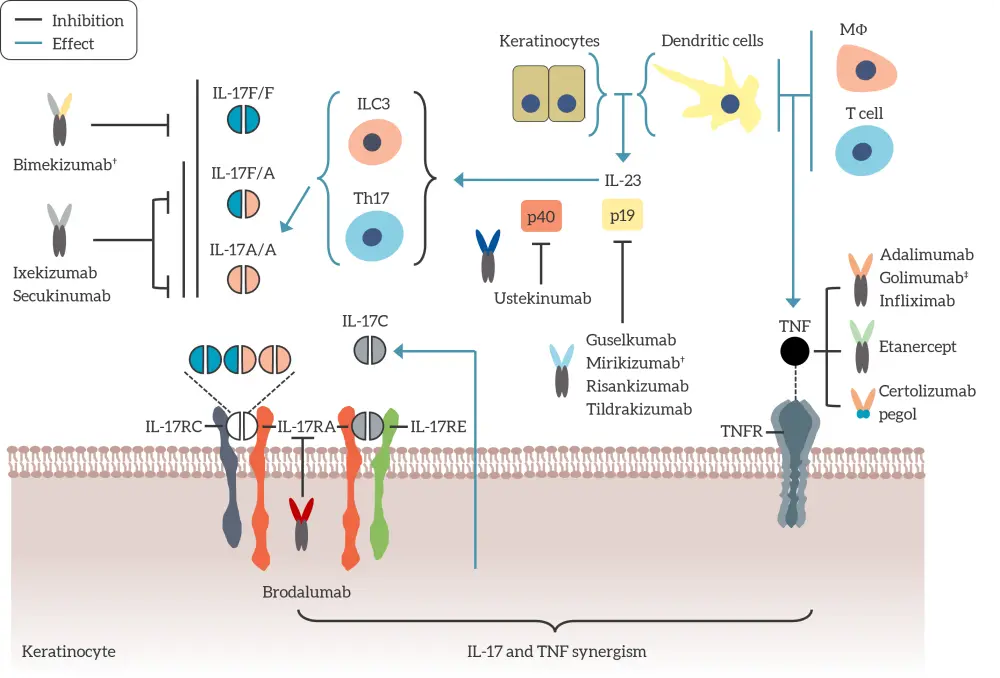

Biologics are mostly recombinant monoclonal antibodies/antibody fragments or receptor fusion proteins, with an ability to treat psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. There are currently 12 biologics in four different classes (anti-TNFα, anti-IL-17, anti-IL-12p40 or -IL-23p40, and anti-IL-23p19) used for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis, plus one more in late phase clinical trials (mirikizumab) and one that is only approved for psoriatic arthritis treatment (golimumab) (Figure 4). Not all patients respond in the same manner to biologics and the risk of treatment failure increases with the number of biologics a patient has received.

Figure 4. Biologics for the treatment of psoriasis and their targets*

IL, interleukin; ILC, innate lymphoid cell; MΦ, macrophage; Th, T helper; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TNFR, tumor necrosis factor receptor.

*Adapted from Griffiths, et al.1

†Bimekizumab has recently been given marketing authorization by the European Commission following a positive opinion from the European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use in June 2021.2

‡Mirikizumab is being assessed in phase III clinical trials and is not yet approved.

§Golimumab is currently only approved for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis.

Conclusion

This overview highlights the global burden of psoriasis, demonstrating how an understanding of this disease burden, including overcoming barriers to treatment access, is vital to improve patient care. The complexity of the pathogenesis of psoriasis is gradually being uncovered and there is consensus that psoriasis is genetically predetermined with various systemic consequences. This may eventually lead to the reclassification of psoriasis into several taxonomically distinct endotypes. This understanding supports the development of a holistic approach in the treatment of psoriasis, factoring in lifestyle management, risk factors, and early introduction of targeted therapies. Although psoriasis cannot be cured, an approach allowing selection of the best personalized treatment plan for patients is certainly possible. Another emerging concept is early intervention and early management of patients diagnosed with psoriasis allowing for screening for multimorbidity, psoriasis education, and behaviour change.

Translational medicine has epitomized psoriasis research, benefiting many patients. However, further research is still needed to understand the mechanism of underlying environmental triggers of psoriasis, the role of the microbiome in the interaction between genetic susceptibility and environmental triggers, and other cytokines and canonical intracellular signaling pathways that may be therapeutically targeted for immediate and long-term management.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with plaque psoriasis do you see per month?